Another Brick In The Wall, part 1

[Roger Waters]Daddy's flown across the ocean

Leaving just a memory.

A snapshot in the family album.

Daddy, what else did you leave for me?

Daddy, what d'ya leave behind for me?

All in all it was just a brick in the wall.

All in all it was all just bricks in the wall.

Song In A Sentence:

Young Pink begins building a mental wall between himself and the world, distancing himself from the pains of life, such as having to grow up without a father.

T he immediate transition from “the Thin Ice” to the hypnotic rhtyhm of “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1” marks the transition from the idea of the wall in theory to the wall in practice. There is no pause between songs, no quiet break for analytical reflection or second-guessing. For Pink, the threat alone of the cracks beneath his feet leads directly to him cementing his first bricks into place. With the groundwork laid and the self-deluding justifcations given by the previous songs, the metaphor of the wall makes its first appearance by name in this, the first and most restrained of the “Brick in the Wall” trilogy. Whereas the previous songs addressed life’s misfortunes, alluding to the defenses that are crucial in order to survive in the world, “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1” compiles all of these instructions and warnings into one uniform and universal symbol.

As imposing as the central metaphor of the Wall may seem, it is not all that difficult to parse. Since my first analysis went online in 1997, I’ve received more than a few e-mails asking for a full explanation of the symbol, but surprisingly there is little to address. The album is so grand and intricate that many fans are intimidated by the thought of interpreting the main symbol of the piece, thinking that there is always more to the metaphor than meets the eye. I personally hold the opposite opinion. If anything, I’d say the main idea behind the Wall is quite simple. As a physical object, a wall is a collection of material that is used as a partition to separate two or more things; the metaphor of the wall as it is used in the album and all subsequent incarnations holds true to this definition, though generally on a metaphysical plane. Because life can be daunting at times, we all have a tendency to distance ourselves from it – television and other activities take our minds off it; alcohol dulls it; drugs alter the reality of it. Coupled with these are coping strategies and what psychoanalysts label defense mechanisms, the unconscious psychological devices we use to cope with any number of problems that we perceive to threaten our self – our ego. As a society, and equally as individuals, we have been conditioned to distance ourselves from pain, even if that pain helps us in the long run. As a result, we create metaphorical bricks in our minds in an attempt to distance ourselves from feeling emotionally raw and vulnerable. As presented in Pink Floyd’s album, over time these individual bricks coalesce into a mental wall that, while helping to temper our psyches, can adversely affect our connection with reality and at times create various syndromes and personality disorders that, in a vicious cycle, further severs that connection with reality. Simply put, the metaphorical wall is nothing more than its physical counterpart: a collection of bricks separating us from something else. In the case of the Wall, that “something else” is life itself.

To this degree, each of the three “Brick in the Wall” songs is about Pink’s further separation from the world; they are, as their titles suggest, more bricks in his wall. In the first of the three, that ever expanding separation is evident right from the beginning with the repetitive guitar riff rippling out into fainter and fainter echoes, suggesting the space that Pink has already built up around his childhood self. This idea of separation is further established from the very first line, with Pink singing “Daddy’s flown across the ocean.” Here, the word “ocean” can be interpreted in both a literal sense – as in the physical bodies of water and land masses that separate England from Italy, where his father was stationed and killed – as well as a metaphorical sense calling to mind the ancient notion that the afterlife lies beyond a vast, uncharted body of water. (For instance, in ancient Greek mythology, the Underworld is divided by a series of six rivers, with the River Styx marking the boundary between Earth and Hades.) For Pink, his Daddy is both physically separated by vast stretches of land and water as well as psychically by an ocean of death. Each successive line hilghlights Pink’s separation from his father, who has left nothing but a memory (an intangible thing existing only in the mind), and “a snapshot in a family album” (a Tantalus-like reminder of what Pink almost had, but which is now always out of reach).

Even time separates Pink from his father, from his original emotions and the bricks they formed. In the first line Pink sings “Daddy [has] flown across the ocean”, the present indicative tense, while only a few lines later he muses in the past tense: “[a]ll in all it was just a brick in the wall.” As with “the Thin Ice,” this shift in verb tense insinuates that rather than serving as a strightforward flashback of events, these childhood songs are actually present-day recollections viewed through the lens of cycnical nostalgia. The shift in tenses might also signal Pink’s nihilistic resignation to what he sees as fate. His wall was started in the past, and it’s something that he cannot change now (or so he believes) or have changed even then. When Pink bitterly asks “Daddy, what else did you leave for me?”, it’s as if he’s referring to his father’s death and the ensuing brick it formed as something he inherited, not consciously created. He was born into his wall – it was created for him – and not vice versa. His only recourse, or so he insinuates by his quiet resignation about them all being “just bricks in the wall” (that “just” diminishing the heft of the bricks’s impact on his life), is to simply carry on the Sysyphus-ian burden of building and maintaining his wall.

Not only does “ABITW 1” introduce the idea of the metaphorical wall, it also establishes the musical thread used by the rest of the “Brick in the Wall” songs. The use of this shared guitar riff as well as the deviation from it in later songs reflects the changing personality of Pink throughout the first half of his journey (disc 1). It can be argued that the repetitious D note played with little derivation in this first song is directly proportional to Pink’s persona at the time. Just as that solitary note gradually emerges out of the final chords of “the Thin Ice,” Pink slowly emerges into self-awareness, realizing the burden that has been placed on him by his father’s death. One can almost hear him monotonously adding a brick with each note, one after the other after the other. Yet such monotony is still unable to repress brief moments of emotional outburst. The absolute bitterness in Waters’ voice as he sings “Daddy, what d’ya leave behind for me?” coupled with the biting accent of the second guitar really illustrate the raw emotion (or at least the remembrance of it) begging to burst through even at this early age, simultaneously foreshadowing a time when these emotions will explode. That brief moment of selfish bitterness also have made some wonder if Pink is going through the second stage of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief – Anger. While he eventually moves beyond blaming his father for his own death, he arguably is never able to move past the emptiness this death left in his life.

Another common theme in the Wall also makes its debut in this first of “Brick” songs: Flying. While “In the Flesh?” technically broached this aeronautical subject with the audio clip of a bomber dropping its payload at the end of the song, “Brick, part 1” addresses the theme directly with the very first line as Pink recounts how “Daddy’s flown across the ocean.” Like so many other metaphors in this album, flying seems to have separate, contradictory meanings. In one instance, flight carries with it all the connotations of adventure and personal escape that one usually associates with the word (the toy airplane in the film sequence for this song, as well as “Nobody Home.”) The flip side is that flying in the Wall also alludes to death, abandonment, and oppresion, from Pink’s father flying off to war and never returning, to the destruction brought by the warplanes in songs like “Goodbye Blue Sky,” to Pink’s mother later telling him that she won’t let him fly, but she might let him sing. In some instances both meanings are simultanesouly applicable, as when the animated dove at the beginning of “Goodbye Blue Sky” takes to the sky in order to escape the marauding cat, only to explode in a mess of blood and flesh as the German war eagle (a symbol of death) is loosed upon the land. Somewhat like the dove, Pink is caught in the middle of the metaphor in “Another Brick, Part 1,” the subject of flying constantly on his mind as if he’s always looking to the sky for freedom, but simultaneously apprehensive of the possible destruction such unbridled freedom can bring.

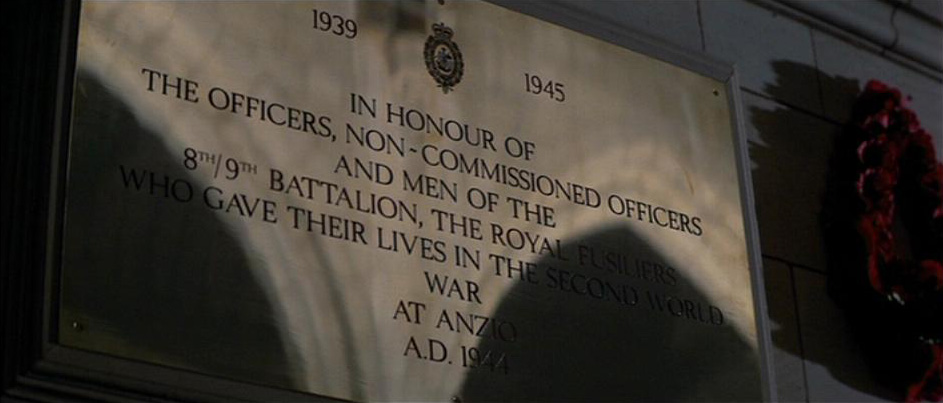

The movie sequence for “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1” is just as haunting and subtle as the album version. While the songs never really give Pink an age, the scenes for this song depict him as being around 5-to-7-years-old, roughly the same time that a person’s psyche really starts to develop a sense of self. According the DVD commentary, Waters said that the scenes within the church were slightly altered from a real event in his life. As a young child, Waters’ grandfather (not mother, as depicted in the movie) took him to the Chapel of the Royal Fusiliers in London to look at the memorial for those fusiliers who lost their lives in World Wars I and II. The event must have etched an indelible mark on the young Waters who remembered finding his father’s name in a book in the chapel.

Like the bricks he internally carries, symbols of war abound throughout the sequence – in the model Lancaster airplane Pink plays with in the church, the General Service and Italy Star medals that he wears, even the chapel itself that serves as a memorial for those Fusiliers who lost their lives in the war. The consequences of war and the personal alienation it creates is displayed no more poignantly than the film sequence’s last half. After his mom drops him off at a city park, Pink is helped onto a spinning merry-go-round, momentarily “adopted” by another child’s father. The joy that lights his face is shortlived, though, with the “adoptive” father shooing him away when young Pink tries to hold his hand. Much like his nihilistic resignation concerning the burden he was born with, little Pink resigns himself to a lonely swing in an empty corner of the playground, watching with equal parts sorrow and envy as the other father’s push their children on the swing set. The emotion is delicate yet raw, a perfect precursor to the unbridled grief of “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 2.”

What Other Floydians Have Said

"I noticed the second time Waters screams 'Daddy, what'd you leave behind for me?' the shot shows Pink looking at his mother. Maybe that's the exact thought that passed through his mind. While other children had fathers who would take them to the playground and hold their hands, all Pink got was an overprotective mother. Maybe he thought his father could have been a wall or a shelter from his mother." - Andrew Taylor