Goodbye Blue Sky

[Young Pink, voiced by Roger's son Harry]Look, mommy. There's an airplane up in the sky.

[David Gilmour]

Di' di' di' did you see the frightened ones?

Di' di' di' did you hear the falling bombs?

Di' di' di' did you ever wonder why we

Had to run for shelter when the

Promise of a brave, new world

Unfurled beneath the clear blue sky?

Di' di' di' did you see the frightened ones?

Di' di' di' did you hear the falling bombs?

The flames are all long gone, but the pain lingers on.

Goodbye, blue sky.

Goodbye, blue sky.

Goodbye. Goodbye.

Song In A Sentence:

The fear and the anxiety felt by a country still transitioning from conflict back to normalcy parallel young adult Pink’s departure from his childhood home.

T here has been a lot of discussion among Floyd fans about “Goodbye Blue Sky,” and not necessarily over some lyrical wordplay or Gerald Scarfe’s beautiful animation for the the film. Along with the inclusion of “When the Tigers Broke Free, Parts 1 and 2,” the placement of BlueSky1″Goodbye Blue Sky” marks a prominent variation between the album and film. In the movie, the song follows the second “Tigers,” while on the album it’s found a bit later, after “Mother.” Although there are certainly narrative and thematic pros and cons for each placement (believe me, I’ve heard them all!), I think the song’s more abstract form lends itself well to both album and film’s sequences.

On the original vinyl, “Goodbye Blue Sky” was the first song on side two of disc one of the double album. In an interview around the album’s release, Waters described the song as being a recap of the first side of album one, summing up Pink’s life to that point. As Waters says, in it’s most simplistic form “it’s remembering one’s childhood and then getting ready to set off into the rest of one’s life.” In this position, the song acts as a fitting transition between the narrator’s adolescent questioning of “Mother” and his more world-weary adult self of “Empty Spaces.” Exemplifying the Wall’s characteristic presentation of a gentle melody juxtaposed against harsh lyrics, or vice versa, much of the music for “Goodbye Blue Sky” is incredibly tranquil, soaring even, only falling into disjointed minors as the lyrics grow darkly paranoid. By Waters’ explanation, one can easily relate to the often contradictory emotions of setting out into the world on one’s own. The chorus of “Ooooh”s prefacing the verses are very heartlifting, offering an aural image of a seemingly limitless sky and equally unlimited possiblities. And yet the “Di’ di’ di’ did you” vocal stutter of the verses undermines the bravado, revealing Pink’s apprehension at striking out into a world that very well may be as cruel as his mother has portrayed. Remembering the symbolism of the color blue as discussed in “the Thin Ice,” Pink is essentially saying goodbye to the “blue sky” of his childhood innocence and the protection of his mother, eager to spread his wings and fly – something Mother never let him do. Though he is equally anxious about crashing. Our protagonist is no longer “Baby Blue,” but is slowly becoming the more emotionally experienced and sexually charged color “Pink.”

As hopeful as the notions of adulthood, self-discovery and blazing a new path into the world are, Pink just can’t seem to shake that “silent reproach of a million tear-stained eyes,” singing here that “the flames are all long gone but the pain lingers on.” Unlike his later self who regresses into his mind where the flames are still burning, at this point in his life Pink realizes that those things that caused him the most mental damage are all in the past – the death of his father is a memory; his repressive schooling days are over [at least in the song’s position on the album]; and he is finally moving away from his mother’s protective reach. Nevertheless, he appears unwilling or unable to let any one of them go. The wounds may have healed, yet the emotional scars still remain. The bricks have been cemented into place.

While it does largely work as a transition piece between adolescence and adulthood on the album, one of the problems with placing “Goodbye Blue Sky” after “Mother” is that the overwhelming war images of the lyrics are somewhat incongruous to that stage of his life. The “frightened ones,” “falling bombs,” and “run[ning] for shelter” just don’t carry across the same overwhelming post-war paranoia as they do when following the equally war-charged “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 2.” The lyrics seem a touch out of place when applied to an older Pink, living in a time when the specter of war had become more of a distant memory than an involuntary, post-traumatic response. Following “Tigers, Part 2,” however, the themes of war and loss feel more applicable to Pink’s own realization of the burdens placed on him by his father, mother, and society as a whole. (Sidenote: Thematics aside for a moment, its earlier position works better for the movie’s pacing in that, had they kept it in its original slot after “Mother,” there would have been two back-to-back animation sequences, first “Goodbye Blue Sky,” then “What Shall We Do Now?,” both of which are more abstract representations of Pink’s story arc. Had it remeaned in its original position, the two animated sequences would have simply kept us away from the live-action narrative of our protagonist for too long.) Earlier placement after “Tigers, Part 2” notwithstanding, “Goodbye Blue Sky” is still very much a song about personal and social transition in its movie placement. Just as England and the rest of the western world were bidding farewell to whatever blue-sky innocence they nostalgically remembered before the war, and were slowly, if not hesitantly, coming to terms with a fractured social milieu perpetually haunted by the depths to which humanity can sink, Pink himself is bidding farewell to his childhood naivete after finding his father’s rubber-stamped death certificate, saying goodbye to a self that could blindly trust the authoritarian figures and social systems structuring his life – a theme of betrayal and revolt that becomes more and more prominent in the next few songs.

As with so many Pink Floyd songs, “Goodbye Blue Sky” illustrates that the ostensibly simple can be deceptively complex. Halfway through the song, the multi-voiced narrator sings how “The promise of a brave, new world / Unfurled beneath the clear blue sky” – a lyric that, at first glance, seems nothing more than well crafted. And yet in that “brave, new world” is a wealth of social and psychological dualism, much of which lies at the very heart of the Wall. For many, the line immediately calls to mind a couple of literary allusions, namely British writer Alduous Huxley’s novel Brave New World, as well as the novel’s namesake from Shakespeare’s play the Tempest, in which the character Miranda states in Act V, Scene I: “How many goodly creatures are there here! / How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, / That has such people in it!” Just as Huxley alludes to Miranda’s speech with a touch of irony in his book title, the phrase “brave new world” as sung by the collective voice of a betrayed humanity in “Goodbye Blue Sky” is delivered with an equal amount of stammering skepticism – an ironic reminder of all the death and destruction that “goodly creatures” create, the pure ugliness of war waged by a supposedly “beauteous mankind.”

Most scholars agree that Huxley’s 1931 novel Brave New World was a response to Futurism, a cultural movement spread over numerous artistic and philosophical niches that sought to turn its back on everything old and in the past, and reveled in all that was daring and new. In many respects, Futurists were seen as modern hedonists, embracing youth, violence, and technology as the center of their avant-garde existence. Writers like Huxley saw mostly vacuous space behind the sexy glitz, and were horrified by the mechanization of nature and the human spirit. Played out to the extreme, they saw Futurism leading to a soulless state of corporate, godlike rule (the denizens of Huxley’s world praise the Almighty Ford) where group thought and materialism reign over individuality and personal expression. And while Futurism as an artistic philosophy had all but run its course by the second World War, Waters possibly equates the failings of that movement with Modernism’s pre-and-post War promises of a more equitable human society via technology. Part of the argument might state that while global corporations promise a more unified world, ultimately the consumerist, faceless culture they promote shares more than a few similarities to Huxley’s vision of a false utopia. In striving to make our lives more personally satisfying through technology, we are practically undermining the very basis of civilization, and thus civility: personal interaction. Furthermore, it’s difficult to separate the technologies that supposedly make our lives more complete with those used to tear down and destroy; something as seemingly innocuous as the teflon coating in non-stick cookware has a history as a friction-reducing coating for parts on the atomic bomb. For someone as wary of authority as is Pink (and, by extension, Waters), modernism’s promise of a “brave, new world” is a double-edged sword that yes, can make life easier, but also yes, can easily destroy it as well.

There’s also a moral double-edge inherent in both Huxley’s and the Wall’s “brave new world.” In Huxley’s novel babies are born from test tubes, trained from birth for their future jobs, and pushed into a homogenized world that has all but destroyed individuality. This future “utopia” is indeed brave and new, though ironically these normally positive adjectives don’t exactly translate to personal, intellectual, and moral advancement. In light of the war theme of “Blue Sky,” it’s fairly easy to see a Huxley-like dystopia in the genetically contrived Aryan nation that Hitler sought to build through his Third Reich. Though easy to see the darkness in others, we often overlook the shadows within ourselves – a lesson Pink will learn by the end of his journey. One could just as easily argue that in the world of Huxley and Waters’ Wall, there is little to no moral distinction between a godlike political force that slaughters millions of Jews and one that can exterminate hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in a few blinding moments, all in the name of military tactics, vengeance, or progress. Taking into account Waters own strong anti-war sentiments, it’s tempting to interpret “Goodbye Blue Sky” as his (and Pink’s) denouncement of the global Powers That Be. After all, we are never told who the “frightened ones” are, or which side is dropping the bombs; in essence, they could be anyone caught in the middle of a political power struggle in which they are mere statistics. That isn’t to say that there isn’t a “right” and “wrong” in war, or that the Allied Forces weren’t entirely justified in most of their actions. But it does suggest that war only perpetuates an endless cycle of violence, controlled by Orwellian systems of government that are, by and large, interchangeable and morally bankrupt, and which use common men and women as chess pieces in their self-serving power struggles. (Such themes are riddled throughout Floyd’s catalog, from the impersonal “lines mov[ing] from side to side” in “Us and Them,” to the childlike war games of the tyrants in “Fletcher Memorial Home.”) So when the narrator innocently asks why “we had to run for shelter when the promise of a brave, new world unfurled beneath the clear, blue sky,” the answer might be because that the promised technological, social and moral “brave, new world” has the potential for being just as corrupt and morally vacuous as the powers being fought against.

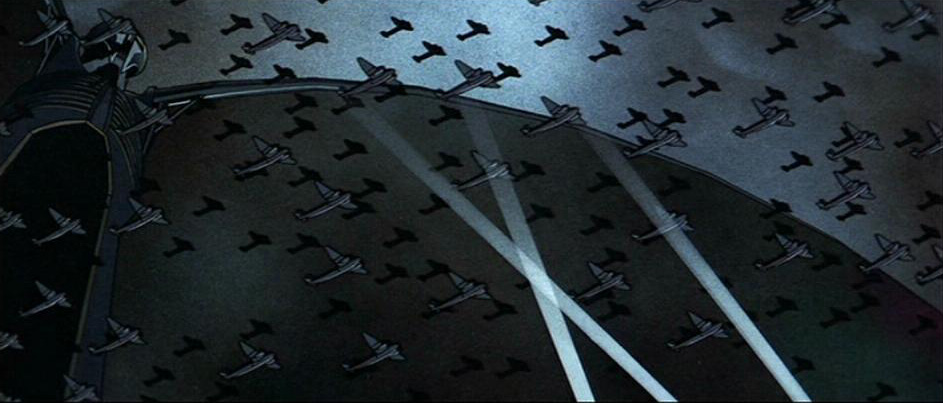

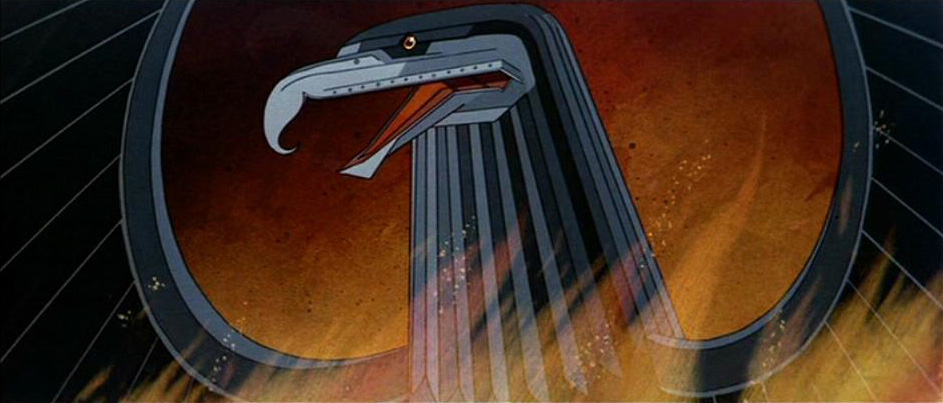

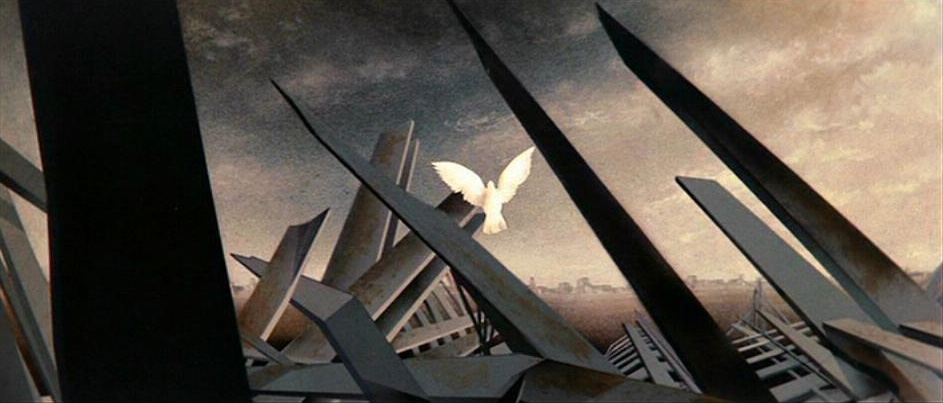

The film sequence for “Goodbye Blue Sky” is a terrific example of just how powerful the medium of animation can be. Artist Gerald Scarfe mentions on the DVD commentary that “Blue Sky” is his favorite bit of animation that he’s done, partly because he lived through the bombing of London and wore the very same gas masks as a child – all stylistically depicted in the sequence – and partly because the piece speaks very much from his political leanings. Ironically, in a story that is by-and-large about Pink, our main character is noticeably absent, a fact that largely mirrors what many see as the character’s narrative absence from the song itself. Granted, the opening shots do show Pink’s Mother resting in the garden with baby Pink presumably in the nearby pram; but apart from these quick shots, all of the characters introduced thus far in the album and movie aren’t present. Rather, the film uses the animation sequences much as the album uses the song: as everything from an abstract representation of both a personal and social mental state, a transition between narrative action, and a comment on the nature of war. The serene shots of Pink’s mother and the pram – the same shots used earlier at the beginning of “the Thin Ice” – act as both a time stamp for the following animation and stand in stark contrast to the images of fire, doom and destruction that is the rest of the sequence. Perhaps suggesting that there is no such thing as a moment of peace even in a peaceful moment (that nihilistic streak that wends its way throughout the album and movie), a cat stalks a dove in the garden but misses his meal as the dove takes to the sky, triggering the switch over to animation. Much like Nazi Germany’s eruption onto the global stage after the western world was just settling from the first World War and the Great Depression, the symbolic bird of peace is torn apart from the inside by a German war eagle, which proceeds to gouge a bloody wound in the English countryside, leaving a sulfurous trail in its wake. The eagle gives way to a domineering war-lord that morphs into a metallic factory churning out legions of bombers flying over London and scaring the gas-mask-wearing “frightened ones” into shelters. These frightened ones are depicted as rodent-like in their amorphous nudity, long-nosed gas masks, and frightful scurrying, prefectly capturing the sense of predator and prey one must have felt at the time, retreating underground for safety. Flying bombers turn into crosses just as the Union Jack (the British Flag) sheds its stripes to reveal a large cross, all symbols of death and sacrifice rather than anything overtly Christian. What’s interesting is that Scarfe uses the same symbol of the white cross for both sides, Enemy and Ally alike, paying tribute to the blood that was shed in all ranks, by all people, both in the name of nationalism and religion. It’s only when the dove of peace reemerges from the shattered ruins of the metal factory / fallen warlord that the dead soldiers are able to find peace in death. It took blood and sacrifice to free that bird of peace, but it itsn’t long before that blood runs down the hill and into a storm drain, ultimately calling to question both the need and lasting effect of an individual’s sacrifice in vainglorious war. It seems that for Waters and the young Pink war can be justified…but that doesn’t mean it is just.

What Other Floydians Have Said

"I think Waters means 'The Brave New World' already appeared with the introduction of the industrial age and is refering to the beginning of the century before the two world wars, when all was hope and joy. With the enormous possibilities of the beginning technological milestones such as flying, etc. Thus he is subsequently noting that 'the promise of the brave new world' leads to fascism, mechanism and the loss of individuality. Portrayed in the fact that two world wars already happened and that a third one is only 'but another power emerging' away.... That Hitler was a product of 'the brave new world' (as much as Pink) and that he could not rise to such power without 'the brave new world' supporting the technological development and basis for human depravation and alienation. So he is blaming the whole world for letting this 'brave new world' lead into the demise and destruction of the innocence of the world as you so rightly argue, though this process began already before the world wars and in fact was the factor leading to the world wars. He puts the blame on the world leaders at the time as well as every single human being for letting it happen. For looking the other way in silent resignation / fear / blind joy of new technology / etc... That people were willingly overlooking the rising fascism in sheer amazement and appreciation of the technical wonders of the time. Both in the past as well as in the present. Thus this song's line is very central to the whole concept of the Wall as it brings a sort of timeless sense of feeling to the work." Jens N. Roved

Webmaster's Addendum: Terrific idea. I think Waters smartly balances the line between anti-industrialism and misanthropy, never leaning too far in either direction. Is he blaming industrialism (the brave new world) for creating this fascist future, or rather, is he blaming mankind's naivete (the PROMISE of a brave new world) for turning such promising ideas into a monster? Is it the fault of these technological wonders themselves, or the human lust for more power inspired by the machines that led to the Hitlers (and, to a FAR lesser extent, the Pinks) of the world? Perhaps a smattering of both, though ultimately I think Waters is an optimist who believes that just as fault might lie with both, so might salvation.

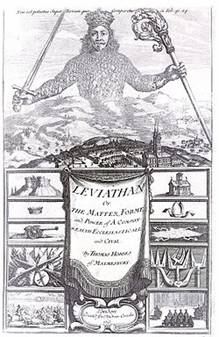

"The monstrous warlord creature in 'Goodbye Blue Sky' looks similar to the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan, drawn by Abraham Bosse. In the film, this creature is shown while you can hear 'Did you see the frightened ones?' As I remember, one important issue in the philosophy of Hobbes’ Leviathan is that the citizens are in fear of the state so that they will not fall back in the feared state of nature which is full of evil and violence. Critics mentioned that this model of society (social contract), which does not mention civil rights but only an early form of law and order, is some kind of model type for a modern tyranny. Hobbes also mentioned that you are not allowed to revolt against the social contract. Moreover, in 1933 with Hitler’s rise to power we saw the possibility to fulfill Hobbes idea of the social contract in a very special way: Ein Volk, ein Führer ("one people, one leader"). Maybe this Leviathan-like-monster of The Wall is a symbol of the totalitarian state of Nazi-Germany. This reminds me of Orwell. Perhaps I am going to over-interpret this image. Otherwise, these are at least coincidences, and this would be again a clever move of Waters and his staff if he were going to explain the area of conflict of individual rights vs. the feeling to be in touch with others. Furthermore, we have again the problem of creating some kind of Utopia (Huxley), of the control of states (Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?), of modern principles and the mistrust in technology and modern development of post-modern times. Well, Waters is a genius." - David Rengeling