Empty Spaces

[Roger Waters]What shall we use to fill the empty spaces

Where we used to talk?

How should I fill the final places?

How should I complete the wall?

Song In A Sentence:

Possibly addressing his estranged wife, possibly addressing himself, a now adult Pink wonders how he will fill the remaining gaps in his mental wall.

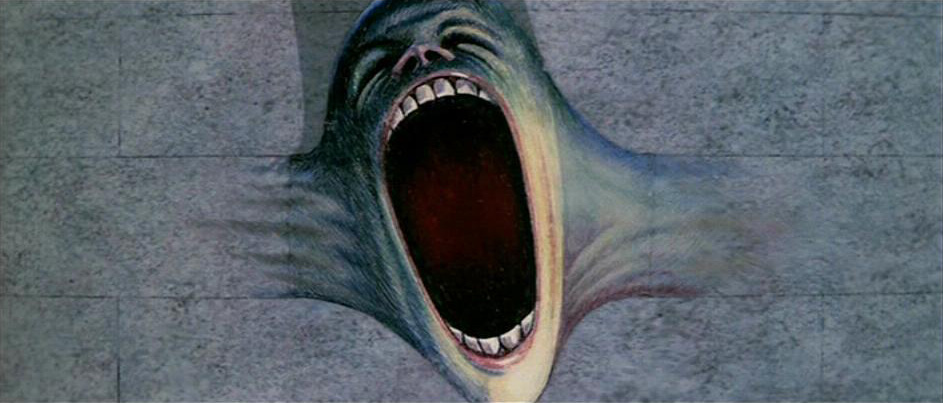

I n its position on the album after “Goodbye Blue Sky,” “Empty Spaces” would seem to serve as a brief narrative transition between the young adult Pink leaving childhood behind and his leap into his newfound personal freedom. Except that the narrative of the song doesn’t quite fit the transitional arc. Instead, what we’re met with is a song whose quavering synthesizers play a similar but more unstable version of the “In the Flesh?” riff set atop a mechanized beat, creating a moment of musical tension set as it is between the haunting “Goodbye Blue Sky” and the brazen “Young Lust.” It’s only when we get to the lyrics of failed communication and completing the wall do we have a sense that rather than acting as a narrative transition, “Empty Spaces” is a brief return to the relative present; a quick reminder of sorts of our protagonist as he currently is, set amid this series of flashbacks depicting how he was.

It might be a bit difficult for first time listeners to know who Pink is addressing with his lyrics. After all, while the movie largely introduced the wife and depicted her infidelity in “Mother,” her character is still out in the periphery at this point in the album, not coming into play until after “Young Lust.” Nevertheless, after a few replays of the album, most listeners get the feeling that Pink is talking – at least in his mind – to the wife with whom he has grown more and more estranged, somewhat rhetorically asking what they should use to fill the gaps in their strained relationship. While the question may seem genuine at first, it’s not until later that we perceive the inherent irony of the lyrics…an irony to which Pink himself is probably oblivious. The empty spaces in Pink’s relationship are self-created, a byproduct of the defensive wall he’s been erecting throughout life. As the wife – or rather, Pink’s internal representation of her – accuses in the album’s climax, “You should’ve talked to me more often than you did. But no! You had to go your own way. Have you broken any homes up lately?” Though the wife is ultimately unfaithful, her actions are solely grounded in her husband’s callous behavior toward her. Further compounding the irony of lamenting the empty spaces he inadvertently caused are Pink’s final questions about filling the “final places” and completing the wall; little does he know that in a song or two, the final bricks of his wall will come courtesy of the communicative void he created in his relationship with his wife.

When one views the song’s album placement in conjunction with the questioning verses reminiscent of “Mother,” an alternate interpretation arises in which Pink’s mother becomes the one being addressed. Having ventured out from his mother’s protective wing, Pink is finally experiencing the real world and discovers it to be more desolate and unfriendly than he was expecting. By this theory, his new inquiries are about how he should fill the void of her protection, of her companionship. Oddly enough, he finds a temporary filler in the sexual frenzy of “Young Lust,” adding yet another Freudian spin to Pink’s relationship with his mother and the influence she’s had on his sexuality. Also by this light, his question on how he should “complete the wall” acts as a sort of continuation of the earlier one in which he wondered if he “should build a wall.”

If, as the story’s protagonist, Pink serves as a Waters’ literary Everyman – one whose life journey reflects the walls and lives of nearly all of humanity – then the “we” in the lyrics of “Empty Spaces” yields a third interpretation. By this view, when Pink sings “What shall we use to fill the empty spaces,” he’s speaking almost in the majestic plural (after all, he will later become a king…or at least a dictator…in his own mind) , wondering on behalf of the human race what we shall use next to fill the void of our postwar, postmodern lives…a theme that is further explored in the movie’s “What Shall We Do Now?”

Adding to the confusion of a quasi-war-like, mechanical beat, an oscillating, off-kilter riff and lyrics that are seemingly unanchored to any one narrative point is a bit of atmospheric mumbling that comes in at the 1 minute 12 second mark. While many simply write off the unintelligible voice as just another sonic layer representative of Pink’s increasingly addled mind, those who play this section backwards are rewarded with a secret message. [Click here to play the section in reverse.] “Congratulations,” Roger Waters begins. “You have just discovered the secret message. Please send your answer to Old Pink in care of the Funny Farm, Chalfont…” At this point, a second person butts in: “Roger, Carolyne’s on the phone.” Leave it to Waters to throw the listener for another loop…or maybe cycle. Though it might be stretching things thin to try and interpret what is obviously Roger Waters’ attempt at humor, those who argue that Pink is instituionalized after his wall comes down at the end of “the Trial” might find some ammunition for their theory here. And yet even if one does attach additional meaning to the message, it doesn’t have to necessarily be all doom and gloom – a foreshadowing of life in either a literal or metaphorical “Funny Farm” (ie, mental institution). The mechanical beat and echoing noise of the song’s intro are reminiscent of the atmosphere of the later concert sequence in the album’s second half, all of which lead to Pink’s trial. So perhaps the secret message wasn’t “sent” from so far in the future, but by a mentally unstable Pink preparing himself for self-reckoning, still searching for the “Answer.”

One more note about the secret message pertains to the mentioning of Roger Waters’ actual wife, Carolyne, who was apparently calling her husband at the time he recorded this bit. Such self-reflexivity is common throughout the album, what with Pink’s father sharing all the same details of Rogers’ own, with many of Waters’ childhood memories serving double-duty as Pink’s own. Here, the mentioning of Waters’ real wife reminds the audience that this story is merely art. Such self-reflexivity is a common characteristic of modernist and postmodernist literature in which the authors intentionally draw the reader out of the story to remind them (among other motives) that what they are reading is artificial, and as such should be read on more levels than just the narrative plane. One of the most classic examples of this can be found in James Joyce’s Ulysses in which the character Molly Bloom, the adulterous wife of the protagonist, seemingly addresses the author directly when she exclaims something to the effect of, “Oh Jamesy. Won’t you take me out of this poo.” Since there is no “James” or “Jamsey” in the story, most readers believe that Molly is addressing Joyce himself, comically asking why he has written her into such a situation. As you can imagine, the effect is jolting. At first the reader is inclined to ask how a character would know that she is just a character in novel? Well, mainly because she is just a character, and as such is saying exactly what she is written to say. Such a revelation forces the reader to step back from the narrative and realize that there is more than story going on here – there is the author’s artistry as well as the multiple metaphoric levels instilled in the piece. The hidden message in “Empty Spaces” has much the same effect, forcing the listener away from the narrative for a moment and reminding us that this is just a piece of art; universally applicable to the human experience, perhaps, but not a slice of life. However, the fact that the second voice calls him Roger while Roger is speaking in the guise of “Pink” reminds the audience that, in a way, this is real – Roger is Pink because he has infused much of his own life and persona into the character. So while the self-reflexive message draws the listener out of the story, the blurring of reality and fiction validates the actuality of the story. The backward message simultaneously shows that while Pink’s specific story is fictional, his metaphorical journey and the wall he creates are universally real.

Interestingly, Waters has been quoted as saying that if it had not been for his wife, Carolyne, and her insistence on communication, he would have ended up as insane as Pink. As we see in the movie, Pink drives his wife away as a result of a lack of communication. But according to Waters, no matter how stubborn he got or how hard he tried to push his wife away, Carolyne would force him to open up and talk. So perhaps the backward message is, above all, a personal “thank you” from Roger to his wife at the time (now ex-wife). It’s little coincidence that just as Old Pink / Waters asks the listener to send in the “answer,” Carolyne is on the phone, wanting to communicate…the very answer both Pink and Waters needed.

What Other Floydians Have Said

It's entirely possible that the wife...wasn't cheating at all. "The man" who answered the phone could have been a brother, old friend / old flame, or even just a sympathetic ear. We don't know who he is; Pink doesn't know who he is. All we know of him is that he is "a man answering" a distant phone. By now Pink is so far up his own ass that he assumes she's is cheating...yet another example of failed communication. - Nick