Another Brick In The Wall, part 2

[Roger Waters & David Gilmour]We don't need no education.

We don't need no thought control.

No dark sarcasm in the classroom.

Teacher leave them kids alone.

Hey! Teacher! Leave them kids alone!

All in all it's just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

[Islington Green School children]

We don't need no education.

We don't need no thought control.

No dark sarcasm in the classroom.

Teacher leave them kids alone.

Hey! Teacher! Leave those kids alone!

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

Song In A Sentence:

Pink continues to speak out against the cruel teachers of his childhood, whom he blames for contributing more bricks to his wall of mental detachment.

T he second and most famous part of the “Brick in the Wall” trilogy directly continues the narrative line and themes begun in “Happiest Days of Our Lives.” If the fantasy in the previous song was the secretly imagined comeuppance that the teacher was said to get when he got home, here it has grown into full revolt as first Waters and Gilmour, and then an auditorioum full of school children, sing an anthem of youthful unrest against the harsh treatment of their cynical teachers. Since its release in 1979, countless adolescents and adults alike have adopted “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” as an anarchistic hymn, using it to strike a blow against what they saw as years of educational oppression. While some apply the song’s biting lyrics to specific kinds of schooling, others use it as a rallying cry against any government mandated form of education. As a result, some countries, such as South Africa, have banned the song from being played on the radio, a few going so far as to place a national ban on both the album and Pink Floyd. However, counter to these extremist views of total educational anarchy, the song was written as an attack against a specific type of learning, that which Waters endured as a child. The lyrics are quite specific to this effect, rebuking those teachers first described in “Happiest Days” who use “thought control” and “dark sarcasm” to mold the school children into mindless drones of society. For Waters, the rote learning and sadistic delivery of his school teachers produced little more than faceless, social clones who knew the definition of an acre yet who could not produce an original, imaginative thought. Accordingly, the rallying cry of “[W]e don’t need no education” can actually be teased in two directions. Firstly, considering that the clause is a double negative, the negatives of “don’t” and “no” cancel each other out, producing an affirmative, as in “We [do] need education,” suggesting that yes, education can be a good thing in developing well-rounded individuals. Secondly, the double negative also acts as rhetorical litotes in this context, used especially to emphasize the point being made, as if Waters is saying “We don’t need this type of education.” In this sense, “Another Brick, Part 2” is not so much a song about complete revolution as it as an anthem about reclaiming one’s individuality; it’s a criticism against the types of teachers and systems that, as in Pink’s case, ridicule an imaginative child for writing poetry.

And yet despite being a song about fighting for individuality, the lyrics are full of apparent conformity. Like the prior “Happiest Days,” gone is any first person singular pronoun – scan the lyrics and you won’t find a mention of “I” at all. Instead, we’re met with a collective “We don’t need no education,” a statement suggesting that even in revolution, conformity is king. Not that that’s always a bad thing. While true that conformity is often depicted in the Wall as personally detrimental, militaristic, and identity-robbing, on the other side of that balance is humanity’s relationship with society. It’s no coincidence that the farther Pink retreats into himself and the more he blocks out the world, the worse off he becomes. When Waters sings via his young semi-autobiographical self that “we don’t need no education / thought control,” he’s more than venting his frustrations over the oppressive education he received; he’s also saying that we, as a society, don’t need this type of education if we’re to evolve past these vitriolic cycles.

Musically speaking, “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” is much more varied and vibrant than the trilogy’s first installment. As mentioned before, the musical styles of the “Brick in the Wall” trilogy reflect the development of Pink. Whereas the music in “Part 1” is subdued and repetitive reflecting Pink’s budding self-awareness, “Part 2” is much more energetic, musically echoing Pink’s lively adolescence and his developing artistic imagination. And just as the band ironically conformed to the most popular musical genre at the time by giving the song a disco beat, the carefully measure beat and still-repetitive rhythm suggest a young Pink also conforming to the conventions of building a wall. The animated guitar solo – a sort of aural outburst of individual expression – breaks through the wall building for a moment, but ultimately the song fades back to the sounds of the school yard and, above all else, the shouting teacher who continues to lord over the children’s lives, yelling “Wrong, do it again!” and “Stand still laddie!”, before reinforcing the infamous lesson that,”If you don’t eat your meat, you can’t have any pudding” (a line possibly alluding to the philosophical notion that you can’t have the good without the bad, that nothing would taste sweet if you didn’t have memories of bitter). Interestingly, the lively but still repetitive song structure (guitar rhythm / verse / chorus) and narrative cycle (teacher / mental revolution / conformity / teacher) rolls perfectly into the dull drone of the phone ringing, briefly foreshadowing the events that take place in the transition between “Young Lust” and “One of My Turns” – events that sour an adult Pink on yet another social instituion: marriage.

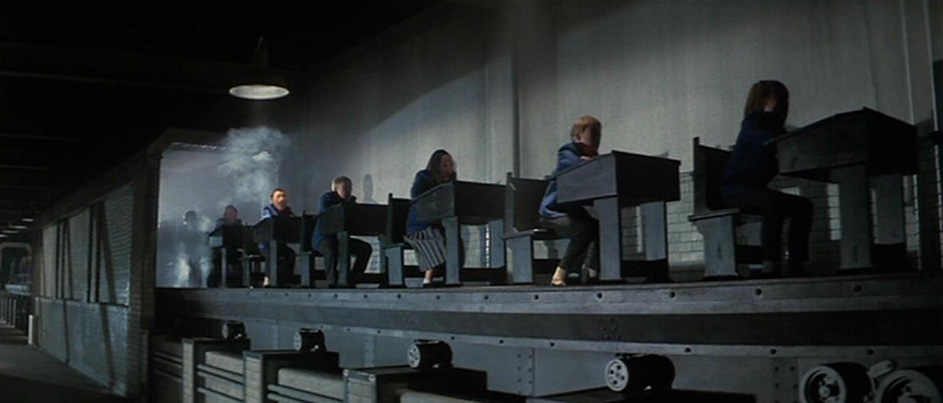

Like the popularity of the song “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2,” the movie sequence is one of the most distinct and well-known pieces in the Pink Floyd video collection. The darkness and cynicism of the set design is due in large part to Gerald Scarfe, who based the factory-like school in the video on some of his previous artwork inspired by his own education. The children march in unison to the same beat, rolling through a machine only to emerge as putty-faced clones void of individuality. Their hollow eyes and mouths evoke a certain amount of revulsion in the viewer. This is deformed humanity, beaten and pressed into a sightless, speechless mass incapable of seeing or speaking out against the oversized meat grinder that eventually minces them all into the same ground beef-like worms. The images are effective in their exaggeration, making the message painfully clear. Oppression of any kind, whether personally or socially, leads to the death of individuality, which in turn leads to soulless homogeneity, which at last leads to decay. Along with the meat’s resemblance to worms, a dominant symbol of decay throughout the album, it’s also interesting to note the heavy use of brick walls all throughout (brick wall tunnels that create the clones; brick wall mazes; brick walls framing the shot of the childrens’ choir) as well as the use of hammers in the machinery. Hammers are a major dichotomous symbol in the Wall possessing both creative and destructive powers, simultaneously beneficial and oppressive. The same hammer that constructs a house has the power to tear it down. Similarly, the hammers in the machines metaphorically create ideal members of society while destroying each child’s individuality. Both natures of the symbolic hammer are explored in greater detail later in the movie and album as Pink slips further into his dementia.

The ideas of conformity in revolution inherent in the song are exemplified to a large extent in the accompanying film footage. Although the children in the second verse sing lyrics of personal rebellion, their unified singing coupled with their symmetrical seating in the film are as eeriely structured as when they march down the hall in lockstep rhythm. Despite their rebellious intentions, they have become just as homogeneous as when they were school clones. Furthermore, like the dual nature of the hammers, what begins as a productive revolution (the regaining of individuality) turns into destructive violence as the children destroy their school and create a funeral pyre for their teacher with the instruments of their past educational repression. This scene of absolute anarchy spawned by the overthrow / absence of an authoritarian figure and the complete destruction of the school’s literal walls (the children’s metaphorical defenses) is evocative of William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies in which a group of school children revert to savagery when the airplane they’re on crashes on a deserted island. Similar to themes explored in Golding’s novel, Waters alludes to both the creative and destructive power found in any absolute. While overly-domineering figures are destructive to personal development, the absence of any authority figure is just as caustic. The dictatorial teacher represses each individual child, but the lack of any education whatsoever is just as harmful. In this sense, living life is like walking a thin wire between two opposite but equally destructive forces. True to the warnings against excess that occasionally pop up throughout the album and movie, the movie sequence for “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” almost seems to adopt a philosophically centrist attitude, its juxtaposed scenes suggesting that leaning too far in one direction leads to tyrannical oppression, while too far in the other direction leads to chaotic mob rule.

While the scenes of the children marching through the factory-school are undoubtedly fantastical, the rebellion that takes place during the guitar solo is much more realistic, thus causing a bit of confusion with some viewers as to whether these events are truly taking place. There are no fantastical elements to the set, and the violence portrayed is certainly feasible. As the scene reaches its crescendo with the children about to throw the teacher onto the bonfire, the viewer is instantaneously pulled out of these dark imaginings to find young Pink rubbing the hand that his teacher struck with the ruler in the sequence for “the Happiest Days of Our Lives.” At this point we are certain that what has just taken place was nothing more than a schoolboy daydream of revenge over hurt pride. It is yet another reminder keep us on our toes lest we fall for Pink’s delusions, something that will become even more prominent – further distorting the line between reality and fantasy -as the story progresses and Pink retreats farther behind his wall.

Strangely, like the first-person “I” in the lyrics, Pink is absent in his own personal fantasy of retribution. Usually one’s daydreams feature the daydreamer as the main character, the hero, the purporter of change; yet Pink is nowhere in sight throughout the factory or rebillion scenes. Rather, he’s relegated himself to the sidelines, an unseen observer enviously watching as the rest of his class fights for personal independence, while he can only dream about it. Already his view of self is so low, his wall so high, that he doesn’t play a part even in his wildest imaginings.

What Other Floydians Have Said

"When the school children are all chanting 'We don't need no education' together in unison, this act, in a way, is MORE conforming than the education they have grown to hate. If you think about it, Roger Waters was saying that even in a revolt against conformity there will still be the presence of conformists, or uniformed followers. The use of the helpless school children is magnificent and proves my point even more. These kids do what they are told! I mean, I read somewhere that Roger got the idea to use a group of kids one day and then BANG, the next day he asked a school if he could come in and BANG, they all agreed and within a short period of time, the entire chorus of children was recorded. No questions asked. Nobody raised a fuss or anything, even the teachers in the school were excited and caught up in the moment without fully understanding what was going on. My point is this: Roger Waters wanted to show how conformity is ever-present, even when we're little, and even when we are rebelling. His point is definitely powerful." - Brad Kaye

Author's Addendum: It was actually Floyd producer Bob Ezrin who originally came up with the idea of recording schoolchildren singing the anthem. Seeing the potential for a radio hit, Ezrin suggested the then-popular disco beat and recorded the children, only approaching the band with the song after his final mix. Needless to say, Waters liked the reworked version and kept it on the album.

"I was listening to a lecture about effects in cinema since its beginning, and the lecturer displayed a few scenes from movies, one of them being a scene from Metropolis (a silent movie from 1927) that shows tens of factory workers walking with submission and perfect matching. The way they walk and the idea behind it made me think immediately of "Another Brick in the Wall 2". The way the people walk in both movies is almost identical. I asked the lecturer about it and he answered that the scene in The Wall is a direct reference to Metropolis. I find it very easy to believe, not only because the lecturer obviously understands much about cinema, but also because merely watching the two scenes can tell that. Even though one movie is black-and-white and the other isn't, both show dark colors and atmosphere. Only the music is very different. Interestingly, it's a German movie, made only a few years before this very nation led millions of people into a situation a million times worse than that." - Noga Syon

"During the end of the scene in which the children overrun the school (a scene that takes place inside of Pink's head and, therefore, could be seen as showing a bit of his take on the world before his wall is firmly in place) Pink sees the children revolting against the repressive influence of the teachers, and summarily destroying the school. They use their books to break the glass case to get the hammers and axes. Now the symbol of the hammer is pervasive in the film, and Pink only embraces this symbol in its destructive capacity towards the end of the film. It represents power, in this case an oppressive force guarded by the teachers. The students, by using their books, a symbol of education, to gain access to this power have found a way early on to take control of their own lives. We see that immediately after the hammers and axes are freed from the glass cabinet, the children begin to smash through a giant wall, thus symbolically freeing themselves from their own walls that threaten to take them over, just as Pink’s wall eventually does him. I read this as Pink viewing the other children overcoming their own walls, and the resentment that he feels adds brick upon brick to his. They use the power that education affords them to rebel and lead, at least in Pink’s eyes, normal lives. So early on, he sees the answer: destroy the walls, his wall is not yet complete and there is still a small bit of hope. However he is unable to join in, and retreats further behind his own wall." - Joseph Gibbs

"The significance of the specific wording of the teacher's "Wrong! Do it again!" shout at the end of the song is more than trifling, in that it illustrates the high expectations of the schoolmaster -- unreasonably high, in that he offers no instruction on how to do it 'right,' only castigation for having gotten it wrong, and an order to 'do it again,' presumably only to risk another rap on the knuckles with the ruler should the student fail yet again to meet his master's expectations." - Gos