Don't Leave Me Now

[Roger Waters]Ooooh babe, don't leave me now.

Don't say it's the end of the road.

Remember the flowers I sent.

I need you, babe

To put through the shredder

In front of my friends.

Ooooh babe, don't leave me now.

How could you go?

When you know how I need you

To beat to a pulp on a Saturday night.

Ooooh babe, don't leave me now.

How can you treat me this way?

Running away.

Ooooh babe.

Why are you running away?

[David Gilmour]

Oooooh Babe

Song In A Sentence:

Pink mentally lashes out at his adulterous wife, alternating between threatening her and begging her to come back to him.

D on’t Leave Me Now” acts as a depressive counterpoint to the manic outburst of “One of My Turns.” The sluggish rhythm of the piano and the reverb-laden synthesizers sonically create the empty spaces stretching in all directions behind Pink’s self-created wall. The atmosphere is a heavy one, emphasized by the sound of slow, labored breathing layered on top of the track. Distressed at the thought of his wife’s infidelity, Pink gives voice to the warring emotions within, in one instant begging his wife to not “say it’s the end of the road”, then seconds later threatening to “beat [her] to a pulp on a Saturday night.” It’s something of a shock for the audience to hear the largely submissive Pink not only conjure up brutal images of physical abuse but also relish in the thought of meting them on his wife. Even the threats of the previous “One of My Turns” had a certain playful, dark humor about them that is missing, or more appropriately, has morphed into something more disturbing in this song. For many, the question then arises as to whether Pink is actually physically abusive to his wife? Are these random beatings that he sings about true? In his interview with Roger Waters, interviewer Tommy Vance aptly (and alliteratively) described Pink as wallowing in the “depths…of deprived depravity” at this point in the album, a mental state one should keep in mind before interpreting the lyrics a bit too literally. Though the listener is invited to draw her or his own conclusions, it’s doubtful that the beatings Pink sings of are real. Rather, it seems they are meant to reflect Pink’s mental state as he puts the final touches to his wall, painting a portrait of a man at his breaking point licking his wounds, so to speak, by fantasizing revenge for being cuckolded and left alone in what he sees a cruel world.

There’s an irony in the tension of Pink’s teetering emotional state, namely in his obliviousness to his own accountability for the strained relationship which he now laments. The very title of the song with its implied subject, “[You] Don’t Leave Me Now,” shifts the action (and thus, the blame for the relationship’s dissolution) onto the wife. Pink is telling her not to leave him, asking her not to “say it’s the end of the road,” asking her “how could you go” and “[h]ow can you treat me this way?” before accusing her of “running away.” As we’ve seen countless times throughout his wall building, Pink fashions himself the hapless victim of yet another brick, shifting the responsibility of his actions onto others. In Pink’s mind, he’s the one whose made all the effort, sending his wife flowers, telling her how much he needs her – claims that are made all the more farcical following on the heels of songs about his sexual promiscuity and personal disconnection from nearly everyone in his life. And while there is some inclination that Pink possibly realizes the personal connections he needs to make in order to begin the ascent from his depression, his guarded self gets the best of him every time he comes close to opening himself up too much. Each time he proclaims “I need you” – a statement teeming with vulnerability and implicating at least some level of dependence – he quickly backtracks and lets his revenge fantasies take over the moment, reasserting his dominance and self-reliance with his imagined threats of physical violence. Like the baby-turned-murderer in the animated sequence for “What Shall We Do Now?”, in the presence of the wall, Pink’s closest moments of apology and endearment are perverted into brutal images of pain and abuse. Even at his emotional lowest, there’s a part of him that wants to be free and is very close to admitting that he actually needs the help of someone else…but ultimately his pride is too precious, his bricks too entrenched.

Although the listener is more than aware by now of all the things that Pink blames for making him guarded, “Don’t Leave Me Now” lyrically hints at a specific, obsessively protective brick in the repetition of the phrase “Oooooh, babe” throughout the song, calling to mind this very same phrase as sung by his mother in songs like “the Thin Ice” and “Mother.” In the earlier song, Mother’s constant referral to Pink as “baby” and “babe” alluded to the emotional infancy her overprotection engendered in her son; here, the phrase is double-edged, at once endearing and patronizing, much like the back-and-forth nature of the song’s lyrics as a whole. Just as the mother sung “Ooooh, babe” as she encircled Pink within her grasp, one can’t help but imagine Pink channeling that very same protective shell, though this time around himself, possibly seeing his mother’s reasoning for not wanting let any “dirty [girls] get through.” It’s as if the seeds of fear that the mother planted within him in the earlier songs have finally come full circle, and are now blossoming into the full-blown neuroses of her son. As if to drive the point home, David Gilmour – the voice of the mother in both “the Thin Ice” and “Mother” – sings the phrase over the song’s musical closing. The way his guitar solo blends seamlessly with the vocals in this last section further illustrates just how much the mother’s over-protection has become a part of Pink’s guarded nature.

Similarly thematic is the “shredder” Pink sings about putting his wife through, as well as the fantasy of “beating [her] to a pulp.” In both instances, shredding the wife and mashing her to a pulp can be said to parallel Pink’s earlier accusations against the British education system. Though not specifically spelled out in the album, the video for “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2” famously depicts a line of faceless students falling into a hamburger grinder, coming out the other end as a meaty pulp. Though the parallel might not be direct or even intentional, the “shredder” and “pulp” evoke ideas of personal humiliation, acting as tools to produce a submissiveness similar to the faceless children in the Wall’s earlier songs and scenes. By this argument, Pink’s fantasies about molding his wife in much the same way that his teachers tried to mold him, coupled with his aforementioned adoption of his mother’s obsessions, indicate that Pink is cyclically becoming the very things that he once detested, foreshadowing his final, most degraded transformation later in the album.

Up until now we’ve approached “Don’t Leave Me Now” as Pink’s imagined discourse with his wife. Yet in his 1979 interview with Tommy Vance, Roger Waters states that, for him at least, Pink doesn’t sing the song “to anybody; it’s not to her [the groupie] and it’s not really to his wife, it’s kind of to anybody. If you like it’s kind of men to women in a way, from that kind of feeling.” By generalizing the song in this way, Waters stresses that Pink’s relationship with his wife is very much the same as the love-hate relationship he has with everything in his life. Yes, the lyrics can be read with his wife as the subject; but the emotional tone can just as applicable to his feelings for the father that left him; the mother that guarded him a little too well; the fame that built him up while tearing him down; even the wall that offered him protection while entombing him. In Pink’s mind, every relationship in his life has been barbed, each one following the same course of expectation and disappointment. As such, “Don’t Leave Me Now” is both plea and accusation addressed to his life in general – just as he starts admitting he needs help, his wall-guarded self steps in and reminds him that ultimately he can’t trust anyone…that in the end, everyone just “run[s] away.”

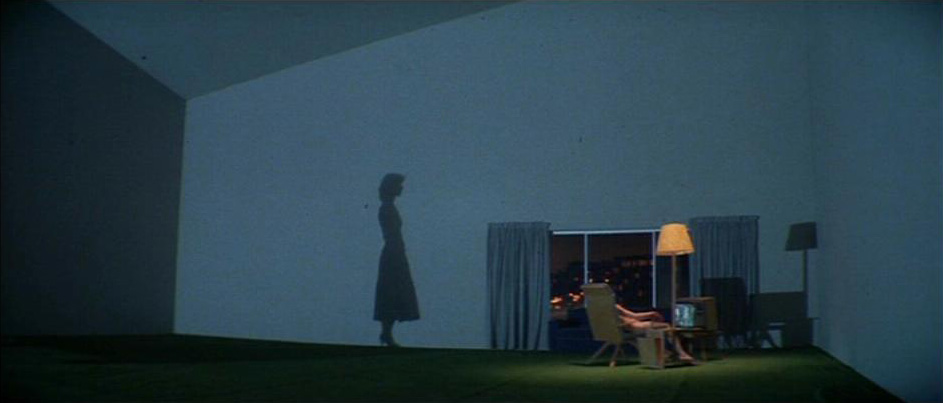

Just as the movie sequence for “One of My Turns” expertly conveyed the lyrical mania of Pink’s emotional outburst, the scenes for “Don’t Leave Me Now” construct dense visual layers that parallel both the growing weight of Pink’s bricks as well as the expansive void behind his wall. The song begins with a close-up of the debris in Pink’s wrecked hotel room, with broken glass, overturned tables, and smashed guitars littering the screen. The chaos of the room perfectly mirrors our protagonist’s mental state as he floats in his private swimming pool sorting through the wreckage of his life. The Christological parallels mentioned in “the Thin Ice” are revisted here, first with a close up of Pink’s blood-soaked hands, conjuring thoughts of strigmata, then with a full screen shot of the “crucified” Pink, his blood dispersing and staining the clear blue water of the swimming pool. The shot is given further weight superimposed as it is over images of Pink’s wife and her lover, the faded image of Pink’s crucifixion standing out in sharp contrast to the almost animalistic movements of the copulating pair. Though it’s already been argued that Pink is a sort of anti-Christ-like figure, the shots indicate that he imagines himself otherwise. In his mind, at least, he is a martyr who is betrayed by the sinful acts of a loved one. Like Jesus is betrayed in the Garden of Gethsemane by the red-headed Judas Iscariot, Pink imagines being betrayed in his marital bed by his red-headed wife. Oblivious to his own accountability for her actions, he sees himself suffering for their sins by means of his own mental crucifixion, bearing the weight of his wife’s transgressions as he almost luridly imagines in vivid detail what surely must be going on in England with the man who answered his home telephone.

That mock-sacrificial blood is given further Christ-like resonance as it drips from his fingers in the next scene, splashing on the hotel carpet next to his chair in cataclysmic echoes. Despite the apparent ordinary reality we find ourselves in, with the Dambusters still playing on the television, the scene is quickly revealed to be another of Pink’s hallucinations. Unlike the littered room that began the song, the hotel room in Pink’s mind is vacuous, sparsely furnished, and, most tellingly, dominated by a large expanse of wall. In the only movie sequence to marry animation with live action, the shadow of Pink’s wife emerges onto the back wall before transforming into a preying mantis, the very name of which sets up the hunting / hunted scenario in which Pink, the self-ascribed victim, is preyed upon by his monstrous wife. The mantis’s face soon transforms into the female flower from “What Shall We Do Now,” which itself is suggestive of a woman’s vaginal lips, a “symbol of womanhood” as Gerald Scarfe mentions on the DVD commentary. Pink cowers in the corner, tortured by both the mantis in front of him and the thoughts of his wife’s adulterous acts superimposed on the screen. Feeling utterly helpless by what he sees to be an unprovoked attack, Pink remains in a fetal position in his imagined hotel room, crouched against giant walls whose blue hue recall that former nickname of innocence, Baby Blue. In his mind, he is as innocent as a crucified Christ suffering on his cross for the world’s transgressions.

In the songs’s final scene, Pink smashes a television with a guitar, striking a symbolic blow against some of the burdens he believes he’s played victim to – his war-torn past (the war-themed movies sparking memories of the past); the materialism of fame (the guitar he uses as a sledgehammer); as well as his relationship with his wife (the romantic couple on screen whose kiss is interrupted by the smashing guitar). This isn’t a rejection of his wall, but a move to embrace it. By destroying the television and thus the symbolic imagery of his life, Pink is essentially turning his back on the life experiences against which he’s fortified himself, rejecting outright the very events he should be accepting as part of himself. In doing so, Pink again fills the role of ironic anti-Christ-like figure, symbolically sacrificing his connection to the external world so that he alone might live.

What Other Floydians Have Said

NickDoctorWho pointed out how the animation of Pink's wife as a scorpion creature both in "Don't Leave Me Now" and "the Trial" somewhat resembles rokurokubi, spirits from Japanese folklore that are thought to be sinister tricksters by nature. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/rokurokubi