The Thin Ice

[David Gilmour]Momma loves her baby, and daddy loves you too.

And the sea may look warm to you babe

And the sky may look blue

Ooooh babe

Ooooh baby blue

Oooooh oooooh babe.

[Roger Waters]

If you should go skating

On the thin ice of modern life

Dragging behind you the silent reproach

Of a million tear-stained eyes

Don't be surprised when a crack in the ice

Appears under your feet.

You slip out of your depth and out of your mind

With your fear flowing out behind you

As you claw the thin ice.

Song In A Sentence:

A newborn Pink is instructed about the emotional turmoil that lies just beneath the calm surface of life.

I f “In the Flesh?” served as the Wall’s conception/birthing narrative, then the “The Thin Ice” is its infancy. Abandoning Pink’s present self for a moment, the song acts as the album’s first true flashback, though not exactly in a traditional sense. The lyrics are less a recollection of past events as they are a glimpse at the emotional ethos that contributed another brick to his early wall.

The wispy piano chords and swelling synthesizers of the song’s first half provide an aural breather from the pounding chaos that is “In the Flesh?” David Gilmour’s soft, almost feminine delivery of the mother’s lullaby-like reassurances that Pink is loved by both mother and father instill a brief sense of hope in both the listener and Pink, especially after the unsettling instructions of “In the Flesh?” concerning the disguises of life. (Sidenote: Though that present tense “and daddy loves you too” might seem out of place, suggesting that Pink’s father is still alive during his infancy, chronologically speaking, Roger’s father – and by extension Pink’s – wasn’t killed until February 1944, five months after his son was born.) This feeling of peace is further compounded by the introduction of “Blue” into the album, an incredibly symbolic color in the album’s first half. Psychoanalytically speaking, blue is considered to be a color of purity, innocence, and life. In dream and literary analysis, the color is often associated with the ocean and sky, both symbols of life and creation. The ocean and water in general have long been symbols of the maternal, of origin. The blue sky is similarly procreative in that it produces the rain which creates and sustains all life on earth, once again feeding the cycle of water=creation=life. Being that blue is most often associated with the color of water, the color frequently takes on the same symbolic connotations. In this instance, young Pink’s appellation, “Baby Blue”, reinforces the idea of the natural innocence of new life, untainted for a moment by the ills of the world. Yet despite the seemingly straight-forward music and lyrics concerning birth and innocence, there are little disturbances in the first half of the song – little ripples on the water’s surface, so to speak, that foreshadow the song’s second, more acrimonious half as well as Pink’s eventual mental decline. In light of what we already know about Pink and the psychological depths to which he will eventually sink, the “blue” in the lyrics could just as much serve as a premonition of his melancholic (blue) existence later in life. Furthermore, the inclusion of such words like “may” and “but” (“and the sea may look warm to you, babe. / And the sky may look blue. / But oooh, babe”) may seem casual on first listen, even insignificant; nevertheless, they plant the seeds of doubt and false-appearances that disrupt the peaceful appearance of the song’s first half. Linguistically speaking, when we as a listener hear “the sky may look blue,” we are trained to listen for a “but” to finish the concession, something that negates the previous statement as in: “The sky may look blue but it’s actually purple” (or something of that nature). The “but” that continues the concession does come, but the rest of the phrase is cut off with the maternal address of “oooh Baby Blue,” as if the speaker is hesitant to continue, allowing the caustic voice of the second half of the song to fill in the missing gaps.

Roger Waters takes up the reins, not bothering at all with word play or sleight of hand, but diving straight in to what the speaker feels is the treachery of “modern life.” Although the symbolism of the second half borrows from that of the first, the latter symbols negate or possibly redefine the previous connotations of blue and water. Whereas in Gilmour’s section water (the sea) is at least spatially associated with warmth (excepting, of course, that auxiliary “may”), in Waters’ half this symbol of innocence and creation is rendered harsh, frozen, even destructive. According to the harsh voice of reality, that symbol of life inexorably can also be the very thing that takes life away: The rain that sustains all life on earth can also annihilate it in a single, torrential flood. Likewise, the maternal waters that foster a new life can change, freeze over, and abort or abandon the life it has just created. Such is the life into which Pink enters. What he thought to be a warm, nurturing ocean turned out to be cold and sterile; the loving mother and the embracing life have become frozen and unyielding. The “sea may look warm” but it is, in actuality, a layer of thin ice covering a frigid landscape.

According to psychoanalytic / literary theory, water is often a symbol of a person’s mental landscape, with images of deep, unfathomable water frequently connected with the unconscious mind – that part of the psyche that houses the majority of a person’s most basic and unrealized self. In this sense, a person’s mind has been compared to an iceberg: he is conscious of the 1/8th of his persona that juts out from the water and oblivious to the 7/8th of his personality’s submerged base. Accordingly, the upper part of Pink’s psyche is frozen over with thin ice, illustrating (or perhaps foreshadowing) the rigid and unemotional person he is or will become. At the same time, it’s this very thin layer of ice that keeps him from slipping into the uncharted depths of his subconscious, an action that would (and will) lead to some measure of insanity as a result of being submerged in his repressed and unrealized emotions.

Yet it’s not just Pink’s own weight that causes the ice of life to crack. Despite the idea that being born is akin to starting life tabula rasa, with a clean slate, according to the speaker, one is automatically subject to the “silent reproach of a million tear-stained eyes” – that is, the generations that precede us, that produced us. There’s an Old Testament idea that the sins of the father are visited upon the son; the narrative voice of “the Thin Ice” couldn’t agree more, insinuating that not only must we carry our own emotional baggage across the thin ice of modern life, but also the baggage of those who came before us…weight that we might not have asked for but nevertheless inherit (such as, in this case, the death of Pink’s father).

So who is this unidentified speaker offering both lullaby and nightmare? Some say it is the callous voice of reality, or experience, those apparent antiheses of innocence. However, I’d opt for it being the voice of Pink’s Mother…though not necessarily Pink’s Mother. We must remember that the Wall is, by and large, a story about Pink told nearly from cover-to-cover from his point of view. Even when another character is speaking, as they occasionally do throughout the album, it’s always through the filter of Pink’s pesonal feelings about them. Their words and thoughts aren’t so much their own as an amalgamated representation of what Pink thinks they might have said or thought, or the implied message Pink assembled from their actions. After making it through the album a few times, we understand that Pink believes his mother was loving to the point of being stifling, protective to the point of being oppressive. Whether in actuality his mother really was this overbearing, we never really know. What we do know, however, is that this is exactly how Pink thought of her, both as matriarch and as jailor. Even when given a voice in songs like “The Thin Ice” and the later “Mother,” that voice isn’t necessarily the Mother’s own, but rather the voice provided by Pink, rife with his pent-up feelings about her. And so what is ostensibly a flashback song about Pink’s childhood is actually his reflection on the fear and cynicism he felt his mother unduly instilled in him at an early age, or maybe even a desire, of sorts, for the kinds of things he wishes his mother had prepared him for – the bitter cold nature of reality and that thin, metaphoric layer of ice keeping us alive and sane.

If the song’s lyrics are an accurate representation of the Mother’s pessimistic voice, then it’s easy to find the early impetus of Pink’s wall; with the message that one is completely vulnerable in life, subject to the unfair weight of previous generations and the potentially all-consuming fissures of a victimizing existence, the alternative of building up a protective shell to protect one from the whims of a cruel, cold world would be all the more appealing. If, on the the other hand, the narrative voice is simply an extension of Pink’s own, the lyrics are like personal justification after the fact…as if in reflecting on the past, the adult Pink is trying to rationalize his wall by saying that without it he would have fallen through the thin ice and been devoured by reality anyway. The irony is that the weight of Pink’s self-imposed bricks are a large cause for the cracks in his mental ice – that rather than protecting him from the dark depths lying beneath that thin veneer of sanity, his wall eventually caused him to break on through.

A quick note on another bit of interesting lyric is the use of the word “claw” for the second time in just as many songs. Not only are there animalistic connotations to the word, but also a bit of inherent violence, as well. “Clawing” is not something done casually, but something you resort to when your back is up against the wall (no pun intended), akin to a base instinct. In the first instance, the verb is a means of self-discovery, “claw[ing] your way through this disguise,” suggesting that this business of tearing down walls isn’t just an intellectual game, but something that will no doubt leave you emtionally battered and bruised. In the second use here in “the Thin Ice,” claw is again instinctual, fear-driven, all the sorts of things you’ll do to keep your head above the water, to stay sane. It’s as if Pink (or Waters…or both) is suggesting that no matter how civilized we think we’ve become, no matter how evolved, that life itself is a crude endeavor in which we must often resort to our baser, more animalistic selves in order to survive.

True to the disjointed tone of the song, the movie sequence for “the Thin Ice” starts by pitting Gilmour’s lyrics about parental love and the warm sea with grisly images of war, death and dismemberment. According to Gerald Scarfe on the DVD commentary, the post-war scenes were directly inspired by the work of Robert Capa, a photographer famous for his unflinching war photographs, most notably his pictures from the D-Day invasion at Normandy. Using Capa’s photos as a base, Alan Parker captures the absolute brutality of war while focusing on the human subtleties of the individuals who make up an army. One example of this macrocosm / microcosm effect takes place at the beginning of the song: As the haunting piano chords creep in, the scene switches from a pool of the collective blood of soldiers to a landscape desolated by war. When Gilmour begins with “Mama loves her baby,” the scene switches from the desolated landscape to a shot of a soldier pulling a blanket over the exposed arm of a wounded man being carried off on a stretcher. The scene of nurturing stands out against the previous and subsequent shots of devastation and ruin, reflecting the contradiction between comfort and pain in the lyrics of the first half of the song. These scenes also underscore what was mentioned previously about the “may” and “but” featured in Gilmour’s half of the song, calling into question the very nature of war, as if the famously anti-war-activist Waters is asking “How can mother and father claim to love their babies while sending them off to die like this?” Also recalling the dichotomous symbolism of water is the soldier slowly being consumed by the sand and tides on the beach, a nearly literal representation of Genesis 3:19 which states that “you are dirt, and to dirt you shall return.”

In the final war shot of the song, a long line of soldiers march single file from screen left to right, walking from daylight into a consuming mist that blurs them from sight. The scene appropriately fades into a shot of Pink’s hotel room and the rock star’s current state of an all-consuming depression and dementia, being erased of all identity much like the soldiers marching one by one into the unrelenting mist. Fading between the two scenes offers another parallel comparing the desolation of war to the emptiness and personal devastation of Pink’s life; although it might seem flippant to compare the gravity of war with the triviality of one man’s life, war itself is spawned from personal instabilities (eg. Hitler’s own obsessions) and is little more than “glorified” killing over property and “moral right.” Apart from scale, the violence of war is little different than that in an individual’s life, a violence instilled from the earliest of ages as apparent by the cartoon cat and mouse in “Tom & Jerry” battling on the television in Pink’s hotel room.

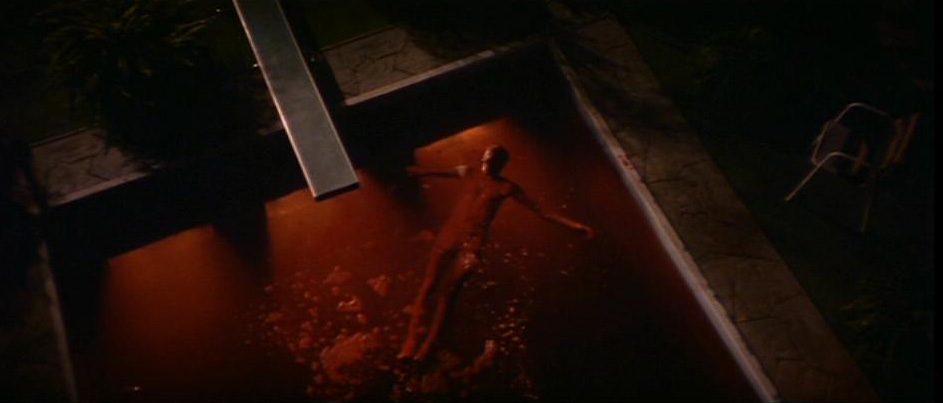

Just as Gilmour’s soothing voice contrasts with the images of war’s bloody aftermath, the subsequent slow, composed shot through Pink’s hotel room contrasts with Waters’ scathing singing, offering a visual bit of calm before the storm of Gilmour’s guitar solo. Water symbolism is brought back into play as the viewer finds Pink floating on the surface of a crystal blue pool. With the onslaught of the blistering guitar solo, the water stylistically turns from blue to red while Pink thrashes around, drowning on thoughts of the war and his father. As with the color blue, red can signify a variety of different things, many of which can be applied to the song and its themes. Red is usually a symbol of raw emotions: passion, anger, frustration, lust, insecurity. On the opposite side, it can also be a symbol of life blood, creation, birth. Both seemingly contradictory meanings are applicable to the film sequence, what with Pink’s chaotic issue into the world (ripped from the tranquil womb, born to a fatherless family, etc.) as well as his final “birth” into madness…all in a blood-red pool. As for the emotional implications of the color, it’s fairly easy to see how all of those raw feelings might fit within the scope of Pink’s mind both as a child and an adult. The metaphoric brick created by the loss of his father is just as weighty in his current state of mind as it was in the past, if not more. As he grows, these repressed feelings begin to boil to the surface more and more, resulting in his infamous “fits”.” Though the fit in “the Thin Ice” is far from that featured in “One of My Turns,” it is nonetheless indicative of the psychoanalytic idea of the indomitable nature of one’s confined feelings. Repressed emotion will only lie in the subconscious for so long before erupting to the surface. The pool scene in “the Thin Ice” is just one tiny crack, one minor eruption of the very emotions that will ultimately boil over and cost Pink his sanity.

Another interesting aspect of the film’s pool sequence is the theological undertones inherent in the imagery. Lying in the water, Pink’s prostrate form is reminiscent of the classical depiction of Jesus’ crucifixion. The blood-red pool further emphasizes the Christological sacrifice, seemingly equating Pink with Christ on some symbolic level. But rather than serving as a typical Christ figure as found throughout Western literature, Pink occupies the realm of literary anti-hero, and so accordingly becomes an anti-Christ figure. (Keep in mind that the “anti-Christ” label used here is not a reference to the specific figure mentioned in the New Testament book of Revelation, but rather a literary figure characterized by traits antithetical to the ideas of Christ propounded by Christian theology. Nor is the use of Christ or anti-Christ/anti-hero figures in literature generally a means of advancing Christian doctrine. Rather, these figures are simply tropes with common ethical and personality characteristics – selfless to the point of self-sacrifice, ideological, oppositional to the social norm, etc. – called “Christ figures” simply because Jesus is one of the most famous examples, even though such figures are found in stories far predating the Christological age. But I digress…) Whereas Christian theology teaches that Jesus was completely selfless and self-sacrificing, arising from his tomb three days after his crucifixion and thereby conquering death and reaffirming his disciples’ faith in God, even a cursory glance at Pink shows that the Christ imagery used in “the Thin Ice” is more ironic than a genuine parallel. Pink is completely selfish (as we will see later in the album / movie), building his wall out of a need to escape rather than aid the world. He dies metaphorically (“Goodbye Cruel World”) in an attempt to elude the external world and is never fully resurrected, existing rather as a self-realized though perpetually fractured, haunted individual, as we saw previously with the post-wall Pink’s similarities to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Mariner. Pink is the antithesis of everything the Scriptural Christ is, and so the symbolic Christological elements inherent in the sequence become tainted. Pink’s “sacrifice” (his building and completion of the wall) is only made for personal reasons; he is the only one covered by his sacrificial blood in the pool…in other words, his sacrifice is in vain. In addition, the color red in the New Testament is often linked with Judas Iscariot who, according to tradition, possessed flame-red hair. Hence, the red of the pool emphasizes both Pink’s selfish “sacrifice” as well as his past, present, and future betrayals, the last of which is when he turns his back on the world and those who love him by escaping behind his wall.

But before we get to that final, selfish act there’s still the business of what Pink sees as the ultimate betrayal perpetrated against him: the loss of his father, as detailed most poignantly in “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1.”

What Other Floydians Have Said

"I was reading your comments on the christological connection (or should I say, antithesis) between Pink and Christ. However, a different perspective occurred to me: Might Pink be connecting his own pain - particularly his sense of betrayal - to that which the crucifixion signifies? Perhaps even, in a sense, the "Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani?" ("My God, my God. Why have you forsaken me?"), the sense of being abandoned by everyone and everything, including - if he exists - God?" - Thomas Wright

Author's Addendum: This is an interesting point, though it should be noted that there is some debate among scholars and believers as to whether Jesus as presented in the Gospel of Matthew was, in fact, bemoaning a sense of betrayal when he cried out the above lament, or was doing the exact opposite. The "My God, my God. Why have you forsaken me?" lament is actually a line from Psalm 22, which (in context) goes on to espouse spiritual acceptance even when the ways of God are unclear. Some purport that the gospel Jesus isn't crying out in alienation at all, but in blind faith. (This would, again, set Pink as an antithetical Christ in that he only feels betrayed in these moments of pain, with no hint of understanding of a divine plan.) Ether way you cut it, I think there is a definite connection.

"In 'The Thin Ice' when pink is thrashing in the (red) water, I noticed a resemblance to the 7th circle of hell, as depicted in Dante's Inferno. In the 7th circle, the violent are tormented by being submerged in a pool of boiling blood barely high enough to breathe. If they go any further, they are fired at by centaurs. Another observation is when pink says 'if you wanna find out what's behind these cold eyes you'll just have to claw your way through this disguise," I think he means you'll have to suffer like he has. Incidentally, the lyrics 'this disguise' and 'through thin ice' [both of which come after 'claw'] fit interchangeably with the other's place, even rhyming properly." - Zolitar

"At the beginning of the film, I think during the cynical part of the 'The Thin Ice,' the camera pans up to a TV showing a Tom and Jerry cartoon. This seems to symbolise perfectly the hierarchical nature of life, as Tom chases Jerry in an authoritative manner up until the dog appears, when Tom then becomes an inferior. This is reflected in 'The Trial' when we see an animation of the doll representing Pink being manipulated by the schoolmaster, who is in turn being manipulated by the 'fat' woman mentioned in 'The Happiest Days of Our Lives.' This in turn represents the authority exerted by the wife who forces the schoolmaster husband to choke down the piece of hard meat. This theme runs throughtout the film." - James Kontargyris