Waiting For The Worms

[Roger Waters]Eins, zwei, drei, alle! [German: One, two, three, all!]

Ooooh, you cannot reach me now

Ooooh, no matter how you try

Goodbye, cruel world, it's over

Walk on by.

[David Gilmour]

Sitting in a bunker here behind my wall

[Roger Waters]

Waiting for the worms to come.

[David Gilmour]

In perfect isolation here behind my wall

[Roger Waters]

Waiting for the worms to come.

Waiting to cut out the deadwood.

Waiting to clean up the city.

Waiting to follow the worms.

Waiting to put on a black shirt.

Waiting to weed out the weaklings.

Waiting to smash in their windows

And kick in their doors.

Waiting for the final solution

To strengthen the strain.

Waiting to follow the worms.

Waiting to turn on the showers

And fire the ovens.

Waiting for the queers and the coons

and the reds and the Jews.

Waiting to follow the worms.

[David Gilmour]

Would you like to see Britannia

Rule again, my friend?

[Roger Waters]

All you have to do is follow the worms.

[David Gilmour]

Would you like to send our colored cousins

Home again, my friend?

[Roger Waters]

All you need to do is follow the worms.

Song In A Sentence:

Pink wars within himself as his insane, dictator rants culminate in shouts of ethnic cleansing, effectively turning him into the very sort of force that killed his father.

I n its position after “In the Flesh” and “Run Like Hell,” the theatrical beginning for “Waiting for the Worms” offers more than a slight repose from the racial slurs and threats of Pink’s latest incarnation. If anything, it shows that despite the dominance of the Hitler-esque figure that’s assumed control over Pink’s mind, there is still a slightly reasonable, somewhat cognizant self trapped beneath. There is a glimmer of the old Pink beneath the furious eyes of his fascist shell, perhaps the very self that his militant persona was threatening in the previous song.

Stepping away from the delusion of autocratic supremacy, Pink, at first in the multiple voices of his splintered personality, recounts his current state behind his self-created defenses. He bids “goodbye [to the] cruel world” once again, though this time his farewell is spoken more out of the sorrowful realization over what he’s done rather than the egotistical need for self-isolation that ended the album’s first half. He has discovered that his “perfect isolation” is far from ideal – not the quiet solitude from the insanity of the world that he had imagined, but in reality a vicious war between the opposing forces of his mind. Like so many troops throughout history whose lives are merely chess pieces in the hands of military dictators, he is a solitary soldier trapped behind his “bunker,” not so much lamenting his situation as he is accepting of it. He waits for the imminent death and decay (the dictatorial voice that continually interrupts his musings) that he knows must surely come rather than hoping for a way out. Yet despite the fact that Pink is doubtful of his fate and that his dictator persona resumes full control over his mind only a few verses into the song, the very continued existence of this underlying authentic self hints at the potential for change and eventual rebellion over the worms of decay.

But for the time being the fascist self resumes control over Pink’s mind and the rest of the song. Just as “In the Flesh” socially paralleled the first stages of Hitler’s rule with the labeling of “outsiders,” and “Run Like Hell” represented the next step, recalling Kristallnacht and the removal of Jews into the ghettos, “Waiting for the Worms” symbolically depicts the final stages in the buildup to the Holocaust, a period in which over 6 millions Jews and minorities were slaughtered by the ruling Nazi party. In the course of three songs, Pink’s autocratic personality has moved from ethnic branding, to segregation, and finally to minority obliteration, shouting through a megaphone at his audience for nothing short of ethnic cleansing as the baritone voices of his followers punctuate his every decree with the foreboding “waiting.” Fascist Pink has progressed beyond the ethnic slurs and threats of the previous songs; he now promises the wide-spread destruction of those who stand in his way, a promise that cements his transformation into the very despotic, oppressive force that killed his father and stained his life from birth.

The Hitler / World War II parallels are as abundant as they are blatant, from “the final solution,” referencing Nazi Germany’s systematic genocide of European Jews, to “turn[ing] on the showers and fir[ing] the ovens,” alluding to the gas chambers and large ovens that respectively killed and incinerated the bodies of their victims. Other dictators and oppressive regimes are referenced throughout the song, as well, such as the Blackshirts (also known as camicie nere or squadristi), a collective name for fascist paramilitary groups comprised of nationalist intellectuals and former soldiers which Benito Mussolini used between the two World Wars to intimdate and often murder his opponents. Pink’s command to “put on a black shirt,” coupled with the later ruminations about seeing “Britainnia rule again” also call to mind the British Union of Fascists, a political party started in Great Britain in 1932 by former Labour party minister Sir Oswald Mosley. After visiting with Mussolini in 1931, Mosley adopted the Italian leader’s fascist ideology and borrowed heavily from the Blackshirts for his own BUF (British Union of Fascists). A number of BUF principles centered around isolating Britain from the rest of the world in terms of trade, commerce and culture, a very wall-like theme that is all but apparent in Pink’s own nationalistic rants in “Waiting for the Worms.”

Though written from a WWII slant, “Waiting for the Worms” is nevertheless broad enough to address the recurring decay of the human condition throughout history as a result of personal and social isolation. While borrowing lyrical imagery from specific regimes, it is not a song specifically about Hitler and Nazi Germany, nor is it solely about Mussolini or Mosely or any one dictator. Rather, it is about all of these and more. It is a conglomeration of corrupted leaders and fascist ideas, a song that ceases to be about one person, leader or idea and becomes the universal force of oppression that has plagued the egotistical minds of men since the beginning of human history. It is the deceptive impetus of extreme nationalism by which one believes his nation is supreme over others (“would you like to see Britannia rule again?”) or that a group can and should be segregated and annihilated because their ethnicity or beliefs differ from the ruling majority (“would you like to see our colored cousins home again?”). It is the hammer-like drive of creation by which nations rise and men are made famous just as much as it is the worm-like force of decay by which those same countries and men fall and are made infamous.

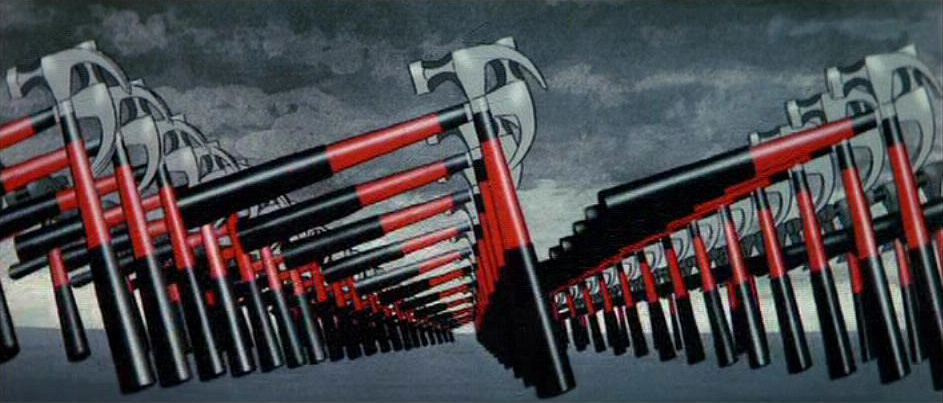

Ultimately, it’s this very force of oppression as well as the endurance of his true persona that snaps Pink back to reality. Roger Waters says in his 1979 interview that as the drugs in Pink’s system wear off, “he keeps flipping backwards and forwards from his real, or his original persona if you like, which is a reasonably kind of humane person, into this waiting-for-the-worms-to-come persona, which…is ready to crush anybody or anything that gets in the way.” Like the decay of his own morality, the song devolves into a cacophany of shouted slurs and threats, with crowd chants of “hammer” growing in volume and ferocity. The feelings of oppression, isolation, hatred, and every other negative feeling associated with the wall culminate in a swirling, chaotic blend, augmented by the heavily distorted reappearance of the guitar riff used and contorted into various forms throughout the album. From both “In the Flesh” versions, the “Another Brick in the Wall” triptych, the guitar solo in “the Thin Ice” and the bridge of “Hey You,” the musical theme that symbolizes all the negative facets of Pink’s wall – the oppression, repression, self-isolation and decay that has stripped away his individuality and turned him into the very sort of monster he once abhorred. Here, the riff is made nearly unbearable by the roiling chant of the crowd and Pink’s own shouted threats, grown so distorted that they become senseless noise. Yet just as the frenzy reaches its climax, it is abruptly eclipsed by old Pink’s final cry for freedom as he screams “Stop!” a singular command of action from the depths of his self-made prison. Old Pink has had enough and is finally ready for change.

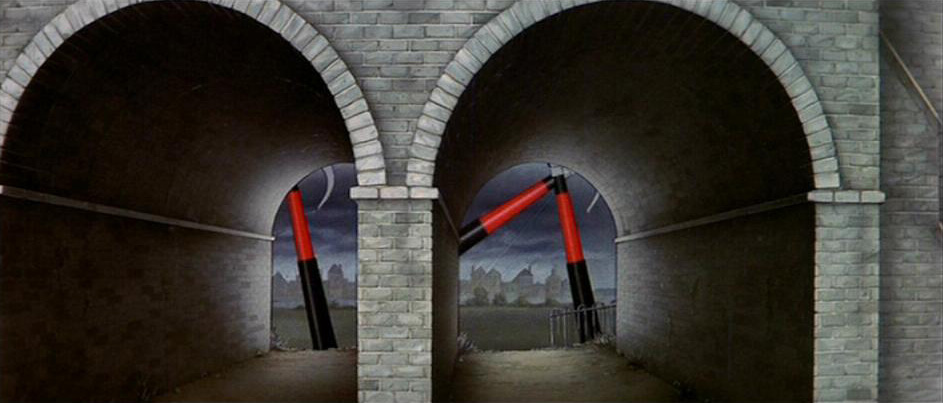

Though much of the song is cut from the movie, the sequence for “Waiting for the Worms” does a brilliant job at visually depicting the foreboding, oppressive tone of the album’s track. The song begins with Pink’s theatrical farewell to the “cruel world,” set over images of the fascist followers carrying the crossed hammer banners and constructing a stage in the middle of a street. The rest of old Pink’s musings are excised and the song proceeds as his dictator self takes the platform with a black megaphone through which he announces his edicts. No longer content to proselytize to his own captive audience, Pink takes to the streets in a seemingly impromptu rally meant to bring his message of fear and isolation to every doorstep in Briatin. For many, the sequence owes much to Oswald Mosley’s October 1936 planned march of his BUF blackshirts through London’s East End, which had a large Jewish population at the time. The march was eventually abandoned after a heavy police presence and an estimated 300,000 anti-fascist protestors turned out to block the BUF’s route in what has come to be known as the Battle of Cable Street. Pink, on the other hand, finds little resistence as residents of the street are quick to lock themselves behind their doors and windows. The rest of the abridged song cycles through various rioting shots, the animation sequence from “What Shall We Do Now?” in which a fascist member bashes in the head of another man, and the famous animated sequence of the army of hammers marching synchronously with the crowd’s “hammer” chant. Buried beneath the chaos, however, are a few shots that, like the appearance of old Pink’s rational voice at the beginning and ending of the song, show that the protagonist’s true self is still extant and capable of redemption. As Pink sings of his entrapment at the beginning of the song, there is a brief shot of a group of concert fans trampling a Pink doll underfoot, followed by an image of that very same doll huddled against a grate. The symbolism of the scene is ominous, depicting how those who are often in the public eye are often thrashed by those they entertain. In this case, in trying to live up to the godlike standards placed upon him by his followers, Pink has lost his individuality – his soul – and has become nothing more than a faceless doll. Yet at the same time, the very inclusion of this image is a welcome sight for the viewer, who has been absorbed by the unrelenting images of Fascist Pink’s rule over the past two songs. If nothing else, these shots are a reminder that there is another, more rational Pink beneath the surface of this Nazi-like incarnation, one who continues to appear throughout the song’s otherwise frightful visuals in brief glimpses, silently screaming for release. Like the album, this rational self finally finds his voice at the climax of the song, screaming “STOP” above the roaring crowd, the marching hammers, and the hate-filled cries of his soon-to-be dethroned dictator self.

What Other Floydians Have Said

"I first heard The Wall while I was in the U.S. Navy in 1979. My friends and I discussed it endlessly, and we came up with some of the same ideas you've expressed here. But only in the past few years have I perhaps caught on to something else. This first came when I saw a retrospective of the Sex Pistols and the whole punk movement of the mid to late 1970's. I recall Johnny Rotten saying how much he and his cohorts hated Pink Floyd. They said that Floyd represented everything they hated about modern music, stadium rock, etc. They wore anti-Floyd t-shirts. The punk movement in Britain was large and violent. There were riots between punks and blacks in Brixton (recalled by the voiceover making slight mention of 'Brixton town hall' in the text). I think that Waters saw the punks as neo-fascists, espousing some of the same ignorant hatreds that Pink's father died fighting against in WWII. The references in 'The Show Must Go On' and 'Waiting for the Worms' are clearly related to fascism, and I think that the group saw it raising its ugly head again in the sometimes incoherent but threatening messages of many punks. So Pink's persona near the end of the album is a slam against this movement and the evil that lies within it." - Paul A. McNaney

"I was just looking at your analysis for 'Waiting for the Worms' and when I was reading about the many Nazi-esque references, another jumped out at me. At the end of the song, when Gilmour sings, 'Would you like to see Britannia rule again, my friend?', he sings it in a stunningly beautiful voice found nowhere else on the album. Then comes Waters with his more sinister, less disguised voice singing, 'All you have to do is follow the worms.' This is followed by another repitition of beauty and sinister suggestions, which is how the Nazis attracted followers. By baiting them with sweet words (restore the Motherland to a respected position, end poverty, etc.), and once they were hooked, unleashing the full force of their evil and hatred upon them (kill the Jews, gays, gypsies, etc.), they managed to attract most of Germany to their cause." - Michael Graham

"The whole song seems to be presented with similar musical instrumentals from past songs in the album. The song opens with a similar musical approach as to that of 'The Show Must Go On,' and recalls 'Goodbye Cruel World' in its lyrics. Possibly to represent Pink's realisation that now that his neo-nazi party has been assembled and has already killed/harmed some of the 'queers and the coons and the reds and the jews,' he can't turn back and that the show (refering to his facist party) must continue their plan. The lyrics to this also seem to refer to this fact. The whole sequence with Pink and his nazi party singing may also be refering back to 'Another Brick In The Wall, Part 2' with the school choir singing. Symbolising the similarity between the school children rioting and burning their teachers, similar to how Pink and his clan are rioting and planning to burn those of other minorities. As sparse as the connection may be, it still sheds a valid comparison. A little further into the song, there is a guitar solo heard. The guitar solo is actually very similar to that used mid-way in 'Hey You,' which also seems to borrow some parts of the one put forward in 'The Thin Ice' and parts of that in 'Comfortably Numb,' as well as (in places) becoming a similar, more aggressive, version of the riff from 'Another Brick In The Wall, Part 1.' Concerning the (possible) references to these past songs could be to represent Pink looking back at his most recent actions in the movie. The song ends with Pink yelling 'STOP!' at the top of his voice, perhaps showing his desire to have these flashbacks stop. He's looking back at his recent madness (symbolised with the guitar solo), and he's not liking it one bit. The hammers marching, accompanied by said guitar solo and images of Pink yelling are a very powerful image, in my opinion." - Liam Elcoat