What Shall We Do Now?

[Roger Waters]What shall we use to fill the empty spaces

Where waves of hunger roar?

Shall we set out across the sea of faces

In search of more and more applause?

Shall we buy a new guitar?

Shall we drive a more powerful car?

Shall we work straight through the night?

Shall we get into fights?

Leave the lights on? Drop bombs?

Do tours of the east? Contract diseases?

Bury bones? Break up homes?

Send flowers by phone?

Take to drink? Go to shrinks?

Give up meat? Rarely sleep?

Keep people as pets?

Train dogs? Race rats?

Fill the attic with cash?

Bury treasure? Store up leisure?

But never relax at all

With our backs to the wall.

Song In A Sentence:

As if in direct answer to Pink wondering how he should fill the final gaps in his wall, a number of modern day vices and other things that keep us from truly connecting with others and ourselves are listed.

W hile many fans assume that “What Shall We Do Now?” is an expanded version of “Empty Spaces” recorded specifically for the movie, the exact oppsite is true. “Do Now?” was actually slated to appear on the album, but was ultimately replaced with a shortened version because it was felt, as Waters explains in his 1979 interview with Tommy Vance, that the song was “quite long, and this side was too long, and there was too much of it.” Along with its length, its easy to see why Waters’ might have been thematically motivated to nix the song from the album. While the lyrics are applicable in a very general way to Pink and his wall, in terms of his narrative arc, our protagonist is ostensibly left on the sidelines as Waters delivers his polemic against a modern, consumerist culture. Thankfully, the song wasn’t scrapped entirely, finding a place in their live shows and taking the place of “Empty Spaces” entirely after “Mother” in the movie. Whereas the shorter version rhetorically asks how to fill and complete the wall, the longer “Do Now?” lists a number of ways to do it.

In the aforementioned interview, Roger Waters goes on to state that “this level of the story is extremely simplistic.” Simplistic, perhaps, but by no means simple. At the core of “What Shall We Do Now?” is a condemnation of a consumer culture run rampant as well as an attack against the notion that a person should be defined by what he owns and what social trends he hollowly maintains. The implication is that when one bases self worth and identity on the external, he or she is never satisfied, but constantly panged by roaring “waves of hunger” for “more and more applause” (that is, more and more acceptance). While we think such things make us stand out in a “sea of faces,” mistakenly believing that we are asserting our individuality through our fancy cars, designer clothes, and workaholic lives, we are in actuality blending in with the rest of the masses who are told to define themselves by these very same social yardsticks. True to the undercurrent of previous songs like “Another Brick in the Wall, Part II,” this attempt at individuality (in this case, materialistic/consumerist individuality) is only achieved through conformity to commercialized social norms. Abandoning your personal idea of self for the one that a collective media says you should be only leads to further dissatisfaction, cycling back into newfound obsessions, new trends, and new, pointless minutiae to govern your life and define who you are.

Yet many have noted that all of the things listed in the song aren’t necessarily detrimental, or even all that noteworthy. Sure, the obsessive need to “buy new guitar[s]” and “drive a more powerful car” is lyrically emblematic of a culture that is never satiated , and “”get[ting] into fights,” drop[ing] bombs” and “break[ing] up homes” can be said to be the morally empty byproduct of a society always demanding more…but things like “giv[ing] up meat,” “leavi[ng ]the lights on,” or “send[ing] flowers by phone?” As Roger Waters states in the previously mentioned interview, it’s about being “obsessed with the idea of being a vegetarian…adopting somebody else’s criteria for yourself without considering them from a position of really being yourself.” These things are not inherently wrong – rather, it’s the obsession with defining one’s self by someone else’s standards that leads to personal and social decay. By mixing the more significant effects with the banal, the commonplace (“train dogs”) with the exaggerated (“Keep people as pets”), the song details just how deeply we embed others’ ideas of individuality and self, both great and small, within our own personas. Without an anchor to our true, individual selves, it’s no wonder so many “take to drink. / Go to shrinks…/ But never relax at all.” Before we know it, we’re sitting “with our backs to the wall” of all the masks we’ve worn and all the junk we’ve adopted as our own.

Although the song veers away a bit from the specific narrative of the Wall, the overall concept is certainly applicable to Pink’s situation. As Pink’s fame and fortunes rise, he further buries himself behind a wall of possessions, becoming more detached from the rest of the world as a result of his personal accumulation. One might even say that he conforms himself to the tired cliche of rock star, donning the celebrity demigod mask that he believes his fans expect him to wear – the very same one Roger Waters was wearing when the seed for the Wall was planted in his mind. It’s also interesting to note that the lyrical list of “What Shall We Do Now?” might be said to ironically mirror Pink’s later obsessive listing of “Nobody Home,” with even a few similarities between the two. “Bury bones” is one of the many activities listed in “Do Now?”, carrying with it quite a few connotations, from the sexual (a euphemism for intercourse) to the possessive (hoarding one’s “bones,” a slang word for money) to the concealing (figuratively burying one’s past indescretions from sight, akin to the saying about hiding one’s skeletons in the closet). By “Nobody Home,” however, Pink sings that “when I’m a good dog they sometimes throw me a bone in,” shifting the figurative meaning of the word to reflect a nostalgic longing for life’s simpler pleasurers and a more basic desire for a merited life. Furthermore, the line directly following about “break[ing] up homes” finds a lyrical parallel during “the Trial” when the wife sarcastically asks Pink if he’s “broken any homes up lately.” While the wife is technically the one who cheats first (at least on the album and in the movie; Pink, no doubt, had his own sexual indiscretions), she was certainly pushed in that direction by the callous inattention of her husband – callous, no doubt, due to the bricks formed by many of the hollow, external definitions of self as addressed in this song.

The movie sequence for “What Shall We Do Now?” takes the original condemnation of an obsessive consumer culture building walls of meaningless junk and amplifies it through a loudspeaker. The screaming face emerging from the wall and the sexually evocative flowers are just two of a number of now iconic images to spring from Gerald Scarfe’s classic interpretation of Waters’ social sermon. The sequence begins with what is one of the most well-known yet often misunderstood pieces of animation from the Wall. Two flowers – one phallic, the other yonic – timidly dance around each other before copulating (for lack of a more discrete word), morphing from humanistic figures to animalistic creatures. The male bites savagely at the female, but is quickly disposed of as the female changes back into a flower, releases her full, radiant glory and snaps up the male in her lips, flying off into the sky as a newly formed bestial creature. Feminist theory would easily characterize this scene as a misogynist attack against dominant women, depicting them as little more than teases-turned-beasts. Such may be the case, but as mentioned often, one must also keep in mind that the Wall is, by and large, a story related from the singular perspective of a very flawed protagonist. And while it was argued earlier that “What Shall We Do Now?” momentarily shifts the lyrical focus away from Pink specifically, many of the accompanying images are still very much of that same disaffected mindset – especially the flower sequence, which follows directly on the heels of Pink’s discovery of his wife’s infidelity. In Pink’s mind, women (or at least his wife) are exactly as the flower sequence implicates – coy at first, even loving and nurturing, but ultimately treacherous and deceptive. From the over-protection of his mother to wife’s betrayal, Pink continually paints himself as the victim of women in his life, forever ravaged by their beastly appetites for his emasculation. Seeing that the feminine flower’s last form is a flying beast graphically similar to that of the German war eagle spreading havoc over the countryside in “Goodbye Blue Sky,” there’s little difference in Pink’s mind between the bricks created by the trauma of global war and that of his warring women.

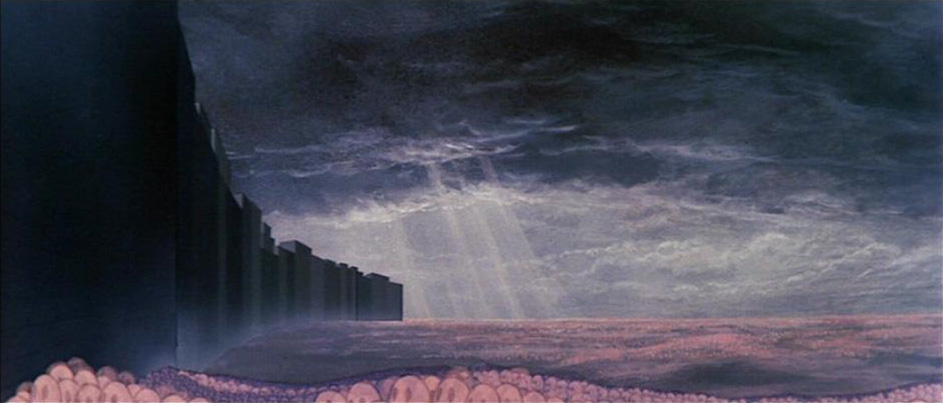

As if spawned by this latest personal injury of infidelity, a wall of materialistic desires bursts onto the screen in the form of high-rise buildings, televisions, radios, Harley Davidson motorcycles, Mercedes, Cadillacs, and BMWs. A “sea of faces” greets the wall of possessions, each one as identityless as the masks worn by the schoolchildren in “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” The massive barrier of consumer greed plunges onward, breaking the peace of the countryside with the screams of the “the people caught up in the wall” (Scarfe, DVD). Everything the wall passes is corrupted. Flowers turn into barbed wire; an innocent infant morphs into a beast and then a uniformed (the same Nazi-inspried uniform of Pink’s fascist regime later in the movie), who bludgeons an innocent bystander to death. Blood splatters the wall. Communal religion is destroyed next as the wall continues its course straight through a church, setting up a “new god” in the form of a casino-like neon building that spews mass-produced neon bricks (Scarfe, DVD).The message is clear, and is as individual as it is universal: These personal and social barriers we build up around us – the cocoons of possessions and obsessions to which we retreat – all but stifle individuality, split our very notions of community and interconnectedness, and eventually lead to social decay, personal degradation, and violence.

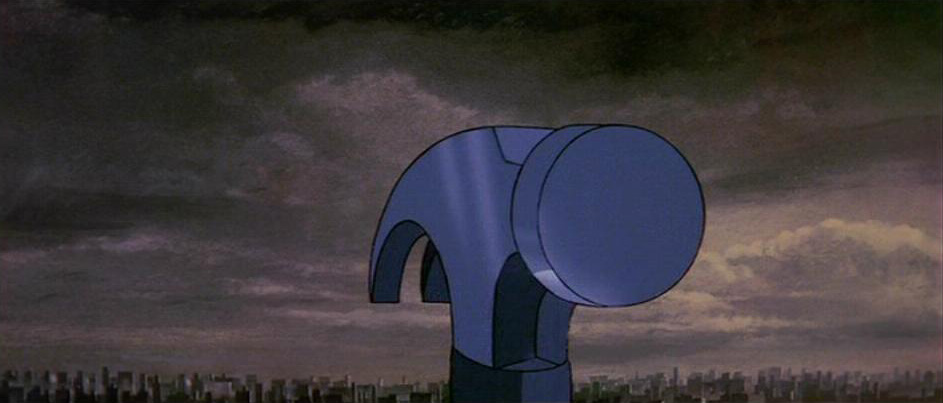

The next few scenes serve double duty, continuing in the same vein of excess as the former sequences while also serving as a sort of running list of Pink’s adult bricks. A pink figure – similar to the doll later associated with Pink specifically in songs like “the Trial” – violently erupts into a curvaceous female shape (the sexual promiscuity of “Young Lust” as well as the feminine “betrayal” in “Mother”), then changes just as quickly into large, feminine dollops of ice cream suggesting the sensual excesses of Pink’s lifestyle. The ice cream then reverts back to the female shape, next turning into a submachine gun (potentially foreshadowing Pink’s violent outbursts later in the film) before becoming a syringe and needle (his drug use), a bass guitar (his musical fame, and possibly an allusion to Roger Waters himself, considering that Waters predominantly played bass in the band), and finally a black BMW (not only an allusion to the expensive possessions garnered by his fame, but also visually evocative of the black car in which Pink later metamorphoses into his dictatorial persona). The song ends with the image of a red fist rising from the ground and turning into a hammer. After seeing how the wall perverts everything in its path, one might view the fist rising from the ground as another perversion of nature similar to the flowers turning into barbed wire. In the presence of the wall, even the earth rises up into an implement of creation (the wall is created) and destruction (personal individuality is destroyed). Another reading of this scene might see the fist rising from the ground as a cyclical omen of nature eventually reclaiming the earth from humanity’s tyrannical reign. Just as grass grows through the asphalt of a parking lot, or weather erodes even the most magnificent of mankind’s creations, so, too, will nature rise up in time and destroy the personal and social walls of humankind.

Linking the animation back with the live action, a hammer smashes a display window, allowing looters to pilfer a range of consumer products. The fact that the items stolen can all be considered luxuries rather than necessities further stresses the idea of violence generated by a wall of rampant consumerism. As the thiefs are hustled into a police wagon, two old women passing by the scene steal items from the broken display window behind the policemen’s backs, suggesting that in a society built with materialistic bricks, no one is totally immune to that inner desire for “more and more.”

What Other Floydians Have Said

"In my opinion, in 'What Shall We Do Now' where they show the wall being built through a chruch, destroying it in the process...that could represent how Syd Barrett used to be a religious person, but after he tried to join a religious group called Sant Saji and was rejected, he soon lost interest in all religion." - Mike McGeary