When the Tigers Broke Free, pt 1

[Roger Waters]It was just before dawn one miserable

Morning in black Forty-Four.

When the forward commander was told to sit tight

When he asked that his men be withdrawn.

And the Generals gave thanks as the other ranks

Held back the enemy tanks for a while.

And the Anzio bridgehead was held for the price

Of a few hundred ordinary lives.

Song In A Sentence:

Pink recalls the last morning of his father’s life, who was killed in action on January 22, 1944 during Battle of Anzio in Italy during World World II.

![]()

A nxious as we are to dive headfirst into the heart of the Wall, let’s take a moment at the beginning to address the song that opens the film and sets the stage for what is to come. Though most people assume “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 1” is the first song of the movie, that honor actually belongs to “The Little Boy That Santa Claus Forgot” as sung by Vera Lynn, part of which can be heard as the camera pans down the long, sterile hotel hallway. [Click to listen to Vera’s song in full.] As heard on the live Floyd album Is There Anybody Out There: The Wall, Live 1980-1981, the band opened their Wall shows with Vera’s war-era classic “We’ll Meet Again” playing over the loudspeakers, but for the movie Waters opted for the potentially more symbolic “Little Boy That Santa Claus Forgot”, the lyrics of which are as follows: “Christmas comes but once a year for every girl and boy / The laughter and the joy / They find in each new toy. / I tell you of the little boy who lives across the way. / This fella’s Christmas is just another day…” At this point, the vacuum cleaner whirs into electric life and “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 1” begins. Yet that’s not the end of Ms. Lynn’s musical cameo. After “Tigers” ends, Vera’s song continues along with the extreme closeup of Pink’s Mickey Mouse watch. “He’s the little boy that Santa Claus forgot” she sings. “And goodness knows he didn’t want a lot. / He sent a note to Santa for some soldiers and a drum. / It broke his little heart when he found Santa hadn’t come. / In the street he envies all those lucky boys…” Once again, the vacuum drowns out the song.

Not heard in the movie, the lyrics continue with “In the street he envies all those lucky boys / Then wandered home to last year’s broken toys. / I’m so sorry for that laddie, / He hasn’t got a daddy. / The little boy that Santa Claus forgot.” Penned in 1937 by Michael Carr, Tommie Connor and and Jimmy Leach, and most memorably sung by Vera Lynn, “The Little Boy..” is a song at once nostalgic and poignant in its quiet depiction of that universal transition from innocence to experience (to borrow a poetic conceit from William Blake). Though ostensibly about a down-on-his-luck boy who receives nothing for Christmas because he’s from an impoverished family in which the father figure is absent, it’s easy to see how the simple story might have had a deeper significance in the context of the war-ravaged era in which it was written. So many of the songs of that time – Vera’s included – were populated with messages of hope barely covering a deeper unease, both for a past that seemed impossibly distant and a future that was as uncertain as it was eventual. (Ms. Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again” is a perfect example of such hopeful uncertainty, but more on that in the “Vera” analysis.) Removed though it is by a few narrative degrees from the war at hand, “The Little Boy…” is still a terrific illustration of the Western world struggling to come to terms with a reality far removed from its political, religious and social ideals. In a perfect world, as a proverb might go, all deserving children get presents at Christmastime regardless of wealth or social standing. The flipside of that adage, just like the flipside of “the Little Boy…”, is that this isn’t a perfect world; childhood naivete is quickly replaced with adulthood realization; fantasy with disenchantment; hope with envy.

While I hesitate in drawing too much of a philosophical connection between the Little Boy and the character of Pink, it’s little wonder that Waters chose to begin Pink’s story with a metaphor about faith and illusion, fantasy and reality. As we find out with each subsequent song, Pink himself is stuck in a self-imposed limbo teetering between a longing for a childhood innocence he never really knew and an unwillingness to face the splintering reality that he has helped shape. Laboring under the delusion of harmless existence, Pink obsesses over everything his childhood was not, and everything that his life has turned out to be. He is the little boy who not only awoke to find out there is no Santa Claus, but awoke to find there’s no such thing as a fair life, as well. In a perfect world, all deserving children get presents at Christmastime. In this world, however, little boys are born without fathers, to overprotective mothers, to personally deadening social systems in a country still reeling from war.

If anything, The Wall is that exactly: a postmodern requiem for both former and present times, a lamenting of the imagined innocence of a pre-war era that will never be whole again (though such yesteryear innocence only exists through the backward lens of nostalgia) while grieving the state of the post-World War II world. In the context of the movie, Vera’s song becomes less a maudlin tale about a down-on-his-luck kid and more a dirge concerning the uncertainties of life fully realized, good and bad. In a way, her message is the very first lesson learned in a highly fragmented, postmodern world: just as there is no Santa Claus, no arbiter of good deeds, there is no guarantee that life will be fair. Accordingly, Pink’s life is bookmarked by post-war fragmentation, both literally and symbolically. The artistic “first chapter” of Pink’s life (i.e. the opening of the movie) is Vera’s song about dreams and disappointment, while the real “first chapter” (“Tigers, Part 1” / “In the Flesh?”) finds Pink fatherless, just like the little boy in Vera’s song. Even more interesting is the vacuum cleaner that interrupts Vera’s song in order to segue into “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 1.” The vacuum is both the object that obstructs Pink’s thoughts in the present as well as the physical embodiment of the void around which he feels his entire life is based. It’s only fitting that Waters, known for his fascination with cycles, leads us from our introduction to Pink via “The Little Boy That Santa Claus Forgot” directly to the vacuum/void, all before taking us to the main root of this abyss…the absent father.

Curiously enough, many Floydians rank “When the Tigers Broke Free” among their favorite Wall songs…despite the fact that the song was not part of the Wall canon until it appeared in the movie three years after the album’s release and subsequent concert tour. (On the DVD commentary, Waters states that “Tigers” was written specifically for the movie, though later he says that it was a song that was just lying around. It’s possible that it was a fragment during the album’s recording, and was finished and polished especially for the movie.) It’s easy to see why many fans gravitate to this song; in an album notoriously known for its ambiguity, “Tigers” is a rare (at least for the Wall), raw, straight-forward narrative more akin to the personal portraits of Pink Floyd’s follow-up album, the Final Cut: A Requiem For the Post-War Dream. While one would think that this dramatic difference in style would make it an ill fit for the the film – especially as the opening piece – some might argue that the song’s unflinching emotionality is exactly what makes it a fantastic beginning. Narratively speaking, the events recounted in the song’s first half take place while Pink is in utero, making the song and its utter lack of irony a great, tonal parallel for Pink’s literal and symbolic pre-birth state. This is a quiescent time when emotion is just that: raw, unfiltered and unimpeded by one’s personal bricks (defense mechanisms). While the narrative voice is grown up and reflective and, in this first part, almost detached – like a historian recounting events of the past – it fits perfectly as a prelude to Pink’s own story as he sits lethargic in his hotel room/womb until his metaphorical birth into narrative action with “In the Flesh?” In many respects, “When the Tigers Broke Free, Part 1” is the proverbial quiet before the storm.

It’s interesting that the tone of the first “Tigers” is so very detached and observational, considering that second half of “Tigers” (featured later in the movie) is much more personally and emotionally charged. Detached though it sounds, there is still a hint of flesh and blood in the lyrics, namely in the subjective adjectives such as “miserable,” “black,” and “ordinary” used to describe the morning just before the battle that will take Pink’s (and Roger Waters’) father’s life. Because the song is so straightforward, the lyrics should need little explanation: the action takes place in a trench at the frontline of the Anzio bridgehead in 1944. Waters states on the movie’s DVD commentary that his father, who served as the model for Pink’s own dad, was 2nd Lieutenant of the 8th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers Company C. The company held the front line in February 1944 when the Germans launched a counterattack against the Allies in an attempt to drive them back to the sea. The fate of the men is still undetermined at this point in the film / album, as is that of the still unborn Pink. Yet history reveals that the Royal Fusiliers Company C was completely destroyed by the counterattack, taking a “few hundred ordinary lives,” among which was Roger’s (and, fictitiously, Pink’s) father.

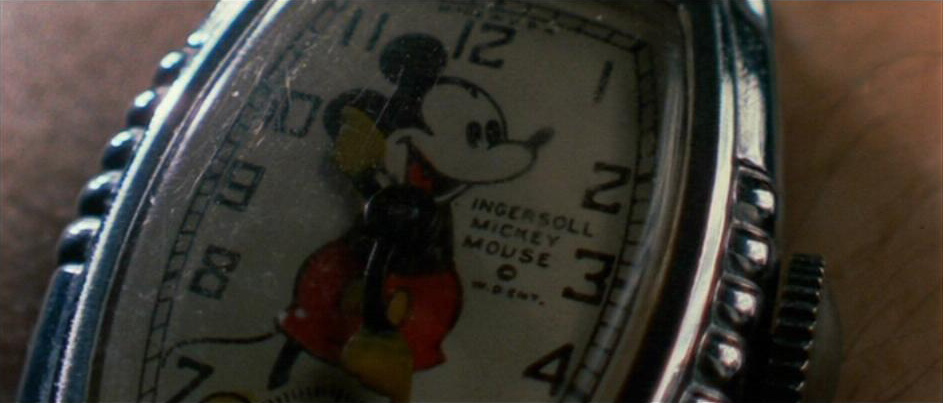

There are quite a few interesting cinematic touches at this early point in the movie, among which are the numerous extreme closeups. The movie opens with a gorgeous long shot of the hotel hallway, at once ghostly and sterile in its absolute barren grayness. The shot is rather evocative of the birth canal leading to the womb/room that Pink currently occupies. From here the viewer is treated to one closeup after another, from Pink’s father lighting his lantern with Lions matches (perhaps suggesting the noble cause and hearts of the Allied forces) to Pink sitting catatonic in his hotel room with a cigarette burned down to his fingers. Every scratch on the glass of Pink’s Mickey Mouse watch is visible (the watch serving as a reminder of the childhood he feels he never truly had) as is every hair on his arm. The effect is both intimate and unnerving; we feel an immediate closeness with Pink’s father as he lights his lantern and a cigarette, utterly alone in a cocoon of darkness as sounds of bombs and guns fire sporadically all around him. Yet at the same time we feel a sense of paranoid scrutiny as the camera details every pore and hair of Pink’s arm. In an instant we become both the rabid media and fans obsessively observing every facet of Pink’s life as well as Pink himself under the world’s microscopic eye as a result of his fame.

We’ve already noted one of the main autobiographical touches Roger incorporated into Pink’s character – that of the father killed in the battle of Anzio during the Second World War – and will later come across even more similarities between Pink and Waters. But along with setting up the Pink / Waters parallel in the “Tiger” lyrics, the first extreme closeup of our main character also introduces another real life model for the fictional rock star: Pink Floyd’s original frontman, Syd Barrett. This shot of a catatonic Pink sitting in his hotel room, oblivious to the world around him – oblivious, even, to the cigarette that has burned down to his fingers – recalls an actual incident that Floyd drummer Nick Mason recounts in his book Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd. During their Fall 1967 tour of the United States following the release of the Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Mason notes that Barrett was becoming more and more erratic, catatonic at times, and that on one occassion “at the Hollywood Hawaiian, a typical LA motel, with floodlit cacti and garish decor, Roger found Syd asleep in a chair with the cigarette burning through his fingers.” Wheras Roger’s life provided a basis for the fictional Pink’s childhood, we’ll find time and again that the adult Pink’s mental free fall from reality at times closely mirrors Syd’s legendary fall from grace.

Along with introducing what will become the first and largest brick in Pink’s wall – his father’s death – the movie sequence for the first “Tigers” also briefly hints at another hugely instrumental moment in the young Pink’s life with the seemingly out-of-place shot of a young boy running across an open rugby field. Far from random, though, the events of this flashback will become another brick in Pink’s wall, and one that he returns to time and again throughout the film, making it just as notable as his father’s death, though oddly in a much more private, individualistic sort of way. Many have speculated that the goalpost with its resemblance to the letter H foreshadows Pink’s drug addiction – particularly to heroin. While this is certainly plausible, one can argue that this particular memory of him running across the playing field as well as the closeup of the Mickey Mouse watch denote the childhood innocence that Pink tries in vain to revisit throughout the narrative. The field is open and limitless save for the goal posts, alluding to the infinite possibilities of life before birth and even during childhood. Yet as every scratch and blemish on Pink’s watch shows, one’s past is etched by every drop and scrape and knick, both literal and metaphoric. Even the childlike innocence of the rugby field memory is underscored by the figure’s very solitude. He is the only visible being in an otherwise empty landscape. Viewed in this light, the scene might not only foreshadow Pink’s drug dependence but also his alienation as a child as the result of losing his father in the war. As such, the sequence creates both a visual and thematic chronology, starting with the father engulfed by the darkness of war which leads to Pink’s pre-and post-birth isolation and eventually spawns the drugged-out, unresponsive man who is so mentally fragmented that he doesn’t even notice that his cigarette has burned down to his fingers, let alone the maid’s knock at his hotel room door.

The conclusion of the calm, pre-album sequences – those cinematic events that take place before the album-proper begins – focuses on both the chains on Pink’s door as well as those preventing a mob of concert-goers from entering the stadium. The chains which held Pink together to this point are about to burst, not only allowing for his birth on the chronological plane, but also for the release of the very emotions and memories against which Pink has built his wall.